Administering the right amount of fluids is crucial in sepsis and septic shock. In critically ill patients, the goal of intravenous fluid therapy is to increase cardiac output to improve both micro- and macro-circulation and tissue oxygen delivery (DO₂). However, in seeking to improve oxygenation, oxygen dilution and fluid overload may occur. The question is not simply “more or less,” but “how much, for whom, and when?”

SEPSIS AND SEPTIC SHOCK

Sepsis is the leading cause of hospital death in the world. Globally, it affects nearly 30 million people annually, with a mortality rate ranging from 15 to more than 50%.

When an infection occurs, the body fights it by releasing chemicals into the bloodstream. Sepsis occurs when this response to the substances is unbalanced, causing organ dysfunction that can damage different systems. Should sepsis progress, it can lead to septic shock.

Therefore, knowing what stage of sepsis our patient is in is crucial. There are initial stages of sepsis where the patient is very tolerant and very responsive to volume and others where they will be intolerant to volume and poorly responsive to it. Hence the importance of knowing in which situation our patient is in order to be able to treat him or her optically.

Please note that the data reflected in this article correspond to adult patients and are different in pediatric patients.

FLUID THERAPY IN THE SEPTIC PATIENT

The goal of hemodynamic optimization is to achieve adequate substrate supply, with adequate oxygen delivery through increased cardiac output. In this role, the most commonly employed strategy has been to increase vascular volume by providing fluids.

The administration of fluids or fluid therapy must take into account the clinical context of the patient and there are several tests that can help us predict the response to fluids. In fact, a 2020 study by Kattan et al. showed that only 50% of critically ill patients will respond to intravenous fluid therapy; furthermore, in those septic patients who were initially responsive, the likelihood of beneficial response dropped to less than 5% after the first 8 hours following resuscitation.

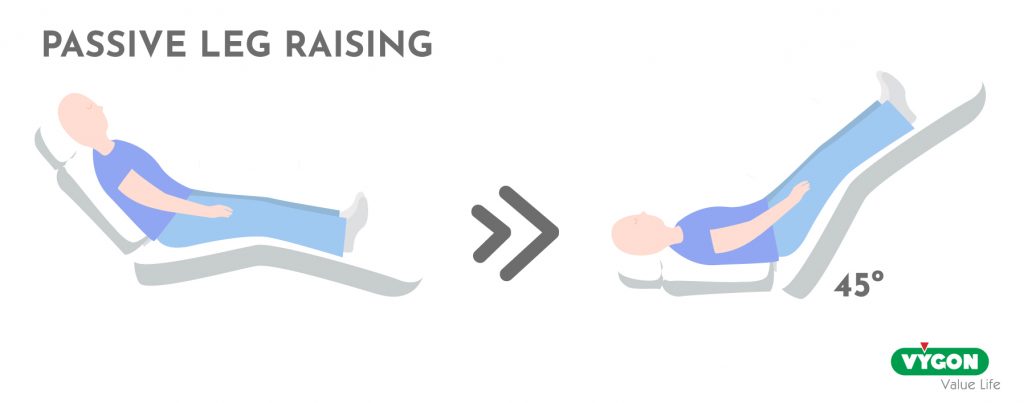

There are different tests that can help us predict the response to fluids, such as the passive leg raising test or the end-expiratory occlusion test.

On the other hand, those who do not tolerate fluids adequately may develop congestion and overload with extra fluid administration.

The latest studies support that there is no relationship between higher intravenous fluid intake and better outcomes and that increased intravascular volume with crystalloids or colloids can cause serious patient complications.

BLOOD LACTATE: A COMPASS FOR RESUSCITATION DECISIONS

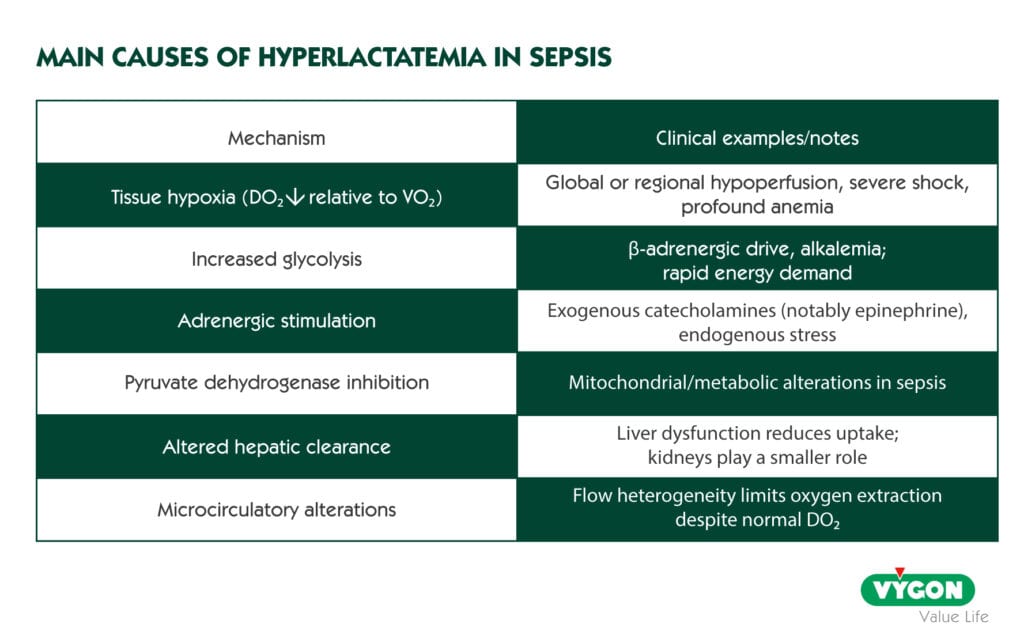

Lactate is a powerful compass for trajectory, not a throttle for minute-to-minute decisions. Mild elevations (>1.5–2 mmol/L) signal altered cellular function and are associated with disease severity and prognosis, but they do not by themselves prove sepsis, nor should they be “chased” with indiscriminate fluids. Hyperlactatemia reflects an imbalance between production and elimination and can arise from tissue hypoxia (DO₂/VO₂ mismatch) and non-hypoxic drivers such as increased glycolysis, β-adrenergic stimulation, pyruvate dehydrogenase inhibition, microcirculatory dysfunction, and reduced hepatic clearance. In short: treat the cause, not the number.

THE IMPORTANCE OF DO2

We speak of DO2 as the amount of oxygen transported per minute in the organism. Its calculation is obtained by multiplying the CO by the arterial oxygen concentration (CaO2).

Normal DO2 levels are between 850 and 1050 ml/min, although it varies according to the pathophysiology of each individual. When DO2 levels are low, they may be a sign of tissue hypoperfusion and lack of adequate tissue oxygenation.

HOW MUCH FLUID SHOULD I ADMINISTER?

Studying hemodynamic parameters by means of a cardiac output monitor is the first step towards understanding the pathophysiological alterations, thus facilitating diagnosis and optimizing treatment.

Changes in cardiac output (CO), stroke volume (SV) and stroke volume variation (SVV) in response to fluid allow us to assess volume response.

To achieve this, goal-guided therapy (GDT), a technique based on continuous monitoring of hemodynamic parameters, allows us to guide treatment and achieve a more appropriate use of fluids.

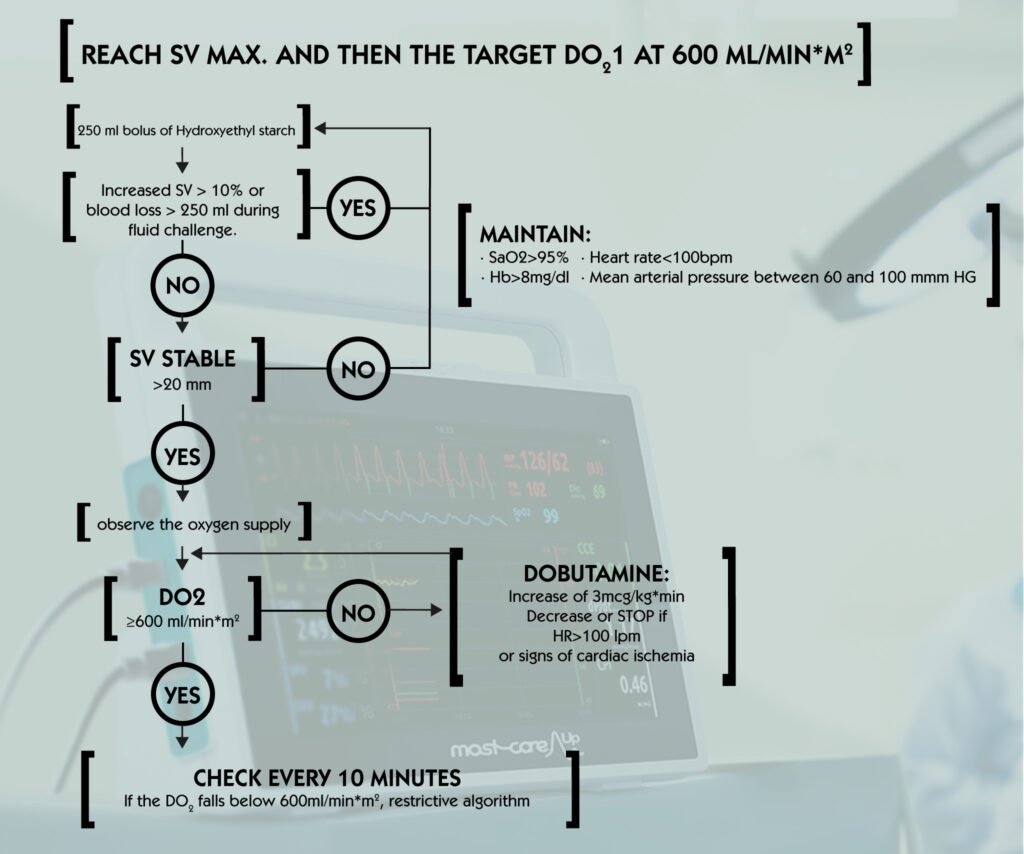

To optimize the rate of oxygen delivery with fluids and inotropes, the European Society of Anesthesia proposes the following:

- Once the systolic volume reaches an optimal level by fluid administration, calculate oxygen delivery index, iDO2.

- If iDO2 is <600 ml/min/m2, introduce an inotrope (dobutamine or dopexamine) to achieve the above goal.

- When infusing, be aware that in the event of tachycardia, cardiac arrhythmia or ischemia, inotropes should never be administered, and if treatment has been started, it should be discontinued as soon as this adverse effect is observed.

A routine and excessive use of fluids is associated with more days of mechanical ventilation or renal injury. In critical cases such as septic patients or septic shock situations, it can also mean the death of the patient.

PUTTING IT TOGETHER: A PRACTICAL BEDSIDE SEQUENCE

- Assess perfusion rapidly: capillary refill time, mental status, skin temperature, urine output, lactate, and ScvO₂/venous gases as available.

- If signs of hypoperfusion and tests suggest fluid responsiveness, give a small bolus (e.g., 250 mL) and reassess stroke volume/cardiac output and perfusion.

- If non-responsive or signs of intolerance (rising venous pressures, pulmonary edema), avoid further fluid. Prioritize vasopressors to maintain perfusion pressure; consider inotropes if flow remains inadequate.

- Trend lactate every 1–2 hours early on to evaluate trajectory; do not expect rapid changes. Integrate with other variables rather than using lactate alone to steer acute interventions.

- Avoid “chasing lactate” when capillary refill is normal and other perfusion indices are adequate—this may lead to unnecessary and potentially harmful interventions.

WE MUST NOT FORGET ABOUT TRANSFUSION

A final concept to consider when treating our patient is transfusion. When through fluid therapy, optimization with drugs does not produce any improvement, and also the hemodynamic status of the patient is as “optimized as possible”, we should consider the possibility of transfusion. In other words, we can improve oxygen transport with hemoglobin, as reflected in Fick’s law.

Once ventilation has been optimized, provide inotropes if necessary, if oxygen supply is compromised, we must consider whether the fluid should be in the form of transfusion product and not as crystalloids or colloids.

For this reason, continuous monitoring of the patient is the key to a correct diagnosis and treatment adapted to the patient’s needs.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Barlow, A., Barlow, B., Tang, N., Shah, B. M., & King, A. E. (2020). Intravenous Fluid Management in Critically Ill Adults: A Review. Critical care nurse, 40(6), e17–e27. https://doi.org/10.4037/ccn2020337

- Kattan, E., Ospina-Tascón, G. A., Teboul, J. L., Castro, R., Cecconi, M., Ferri, G., Bakker, J., Hernández, G., & ANDROMEDA-SHOCK Investigators (2020). Systematic assessment of fluid responsiveness during early septic shock resuscitation: secondary analysis of the ANDROMEDA-SHOCK trial. Critical care (London, England), 24(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-2732-y

- Nieto-Pérez, Orlando Rubén, Sánchez-Díaz, Jesús Salvador, Solórzano-Guerra, Armando, Márquez-Rosales, Eduardo, García-Parra, Oswaldo Francisco, Zamarrón-López, Eder Iván, Deloya-Tomas, Ernesto, Monares-Zepeda, Enrique, Peniche-Moguel, Karla Gabriela, & Carpio-Orantes, Luis del. (2019). Fluidoterapia intravenosa guiada por metas. Medicina interna de México, 35(2), 235-250. Epub 30 de septiembre 2020. https://doi.org/10.24245/mim.v35i2.2337

- Messina, A., Bakker, J., Chew, M., De Backer, D., Hamzaoui, O., Hernandez, G., Myatra, S. N., Monnet, X., Ostermann, M., Pinsky, M., Teboul, J. L., & Cecconi, M. (2022). Pathophysiology of fluid administration in critically ill patients. Intensive care medicine experimental, 10(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-022-00473-4