The administration of fluids is essential for the survival of the critical patient in shock, regardless of the cause of the shock.

This supply occurs to a greater extent during the first hours and days of stay, since it is during these that resuscitation of the patient is carried out, who is frequently admitted to the ICU for shock or hypotension of any etiology.

Fluid therapy is a challenging technique, as there is no formula that works the same for all patients, but requires careful assessment to understand the individual needs of each patient.

The first two questions that any practitioner will ask when faced with fluid therapy are:

What fluid to give?

How much fluid to administer and over how long a period of time?

To answer these questions, the first distinction to make is whether the patient requires maintenance fluids or fluid replacement.

Maintenance fluid therapy

Maintenance fluid therapy is indicated for patients who either cannot drink enough or cannot drink any fluids at all, but nevertheless do not have volume depletion, hypotension or continuous losses.

In addition, the loss is caused by physiological causes such as urine, sweat or respiratory tract.

Replacement fluid therapy

Replacement fluids are intended to replace body fluids and electrolytes whose losses are not only physiological but also include vomiting, diarrhea or severe skin burns.

When designing a fluid management strategy, these two categories need to be considered as a starting point.

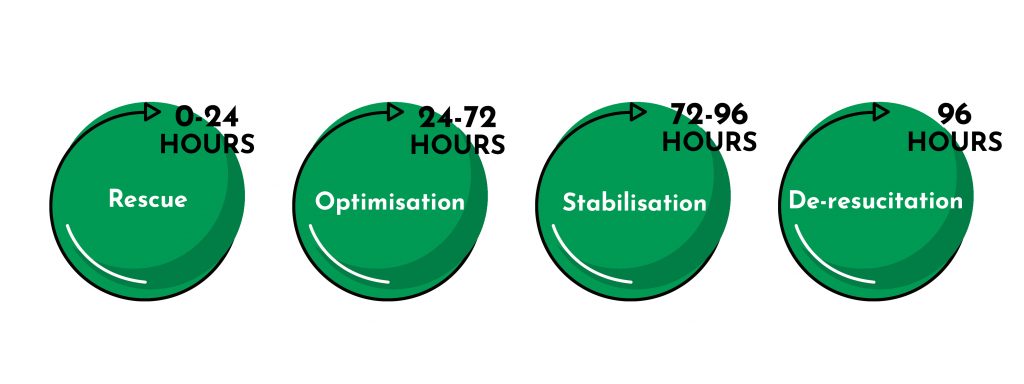

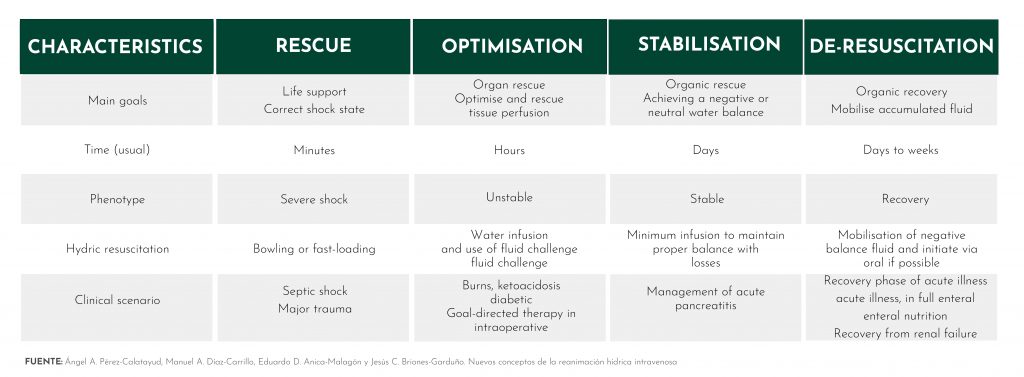

Resuscitation has four phases, which are logically linked to the different clinical phases that we find in fluid therapy during the course of time that the treatment lasts and in which patients experience an improvement in their condition.

To outline these four phases of resuscitation, we will focus on one of the most common and complex clinical scenarios faced by professionals: the patient with septic shock.

This patient is characterised by a first stage showing hyperdynamic shock with decreased systemic vascular resistance due to vasodilatation, increased capillary permeability and severe absolute or relative intravascular hypovolemia.

The 4 phases of intravenous fluid resuscitation are:

Rescue

This phase is characterised by severe vasodilatation leading to low mean arterial pressure and microcirculatory impairment.

It may also be accompanied by high or low cardiac output, in the case of septic shock the cardiac output will be low and accompanied by severe hypovolemia or sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy.

This phase spans from the first minutes of fluid therapy to 24 hours and is characterised by a goal-directed fluid strategy based on early rehydration for stabilisation of tissue hypoperfusion.

It is important to infuse an individualised amount of fluid for each patient. Through the use of hemodynamic monitors, it will be possible to assess the fluid requirement and the patient’s premorbid conditions.

In this phase, fluid administration will significantly increase cardiac output in most cases. However, after the first few fluid boluses, the likelihood of non-response is high. It should be noted that response can only be determined after the bolus has been administered and provided that a monitoring device is used that allows us to calculate cardiac output.

What fluid to give and how much?

In the ‘Surviving Sepsis Campaign’ we find recommendations for fluid therapy in patients with sepsis:

- Septicemic shock and sepsis are medical emergencies and immediate treatment and resuscitation is recommended.

- The first choice of therapy in patients with sepsis will be the administration of at least 30ml/kg of intravenous crystalloids within the first 3 hours.

- Hemodynamic assessments, such as assessment of cardiac function, to determine the type of shock.

- Use of dynamic rather than static variables to predict response to fluid administration.

- Target mean arterial pressure of 65 mm Hg in patients with septicemic shock requiring vasopressors.

- Normalise lactate when elevated as a marker of tissue hypoperfusion.

During resuscitation, constant observation of the patient’s hemodynamic status is necessary to avoid over- or under-treatment.

Optimisation

Once the boluses have been administered and the professional determines that the patient has been ‘rescued’, the optimisation phase begins. This phase starts 24 hours after starting fluid therapy and lasts up to 72 hours.

The objective in this phase is to try to reduce hypovolemia, ensuring an adequate oxygen supply to the organs at risk and thus preventing organ failure due to hypoperfusion or tissue oedema.

Fluid accumulation will determine the severity of the disease and is considered a marker of disease.

The greater the fluid requirement, the more severe the disease and the more likely organ failure.

What fluid to give and how much?

Obviously the clinical context needs to be taken into account, the amount to be given should be related to the cause that has led to septic shock.

Tests to predict fluid responsiveness

As we find a reduction in the hypovolemia index the amount of fluid required will also be less, typically between 5 and 15 ml/kg.

In order to determine the exact amount of fluid to administer, it is important to try to predict the response to fluids, for which we can use two techniques:

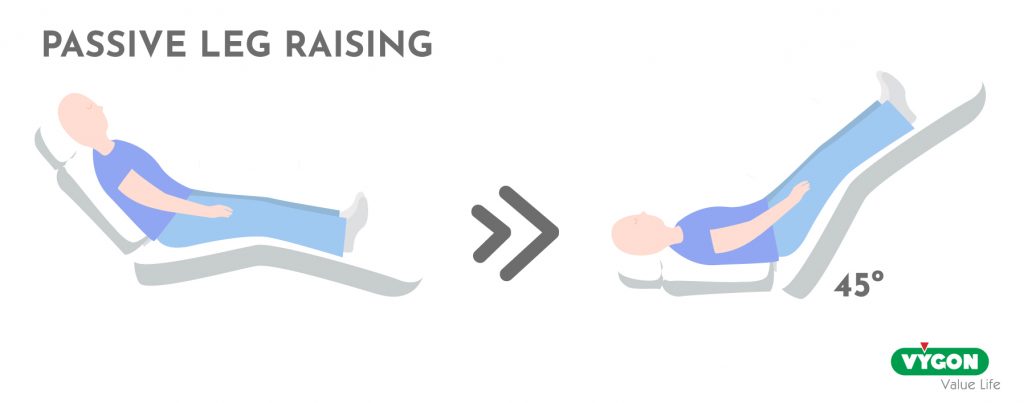

- Passive leg raising test (PELT).

This is performed by starting from a semi-reclined position and moving to a position where the legs are raised 45° and the trunk is kept horizontal.

The transfer of venous blood from the lower extremities and the splanchnic compartment to the cardiac cavities mimics the fluid infusion-induced increase in preload.

- End Expiratory Occlusion Test (EOT)

This consists of stopping mechanical ventilation at the end of expiration for 15 seconds and measuring the resulting changes in cardiac output.

An increase in cardiac output above the 5% threshold indicates preload/fluid responsiveness.

At this stage, the practitioner may also make a decision to withhold fluids based on indices indicating the risk of possible fluid overload.

Indicators of fluid overload risk

Pulmonary insufficiency

Pulmonary insufficiency is one of the worst scenarios for the consequences of fluid overload.

To estimate the pulmonary risk of high fluid infusion we need to know:

- The extravascular lung water index (EVLWI).

- The pulmonary vascular permeability index: this is one of the key factors in determining pulmonary oedema.

Intra-abdominal hypertension

Intra-abdominal hypertension is another common consequence of excessive fluid administration.

Intra-abdominal pressure should be monitored with caution, especially in at-risk patients.

Stabilisation

After 72 hours from the start of fluid therapy, the stabilisation phase begins, which can be extended up to 96 hours from the start of treatment.

At this point, the patient is stable and the aim is to prevent damage to target organs.

Stabilisation is characterised by maintenance water therapy, where the cumulative water balance is neutral or negative, as a sustained positive water balance is associated with a higher mortality rate in septic patients.

What fluid to give and how much?

Maintenance fluid therapy should only be used to meet daily fluid and electrolyte needs.

If the patient receives daily intakes by other routes such as enteral or parenteral nutrition, intravenous fluid therapy will be discontinued.

Resuscitation

Hemodynamic stability has been achieved or 96 hours have passed since treatment began.

In this phase, a negative water balance is sought by restricting intravenous fluids or inducing spontaneous diuresis to restore intrinsic hemodynamic function.

Fluid therapy can save many lives, however, as it is a highly complex treatment it requires a thorough knowledge of the dose-effect relationship as well as the side effects of each fluid in order to personalise the treatment for each patient during the four phases of treatment.

Bibliography

- Teboul JL, Monnet X. “Detección de la capacidad de respuesta al volumen y la falta de respuesta en pacientes de la unidad de cuidados intensivos: dos problemas diferentes, una sola solución. Cuidado crítico. 2009; 13 (4): 175. doi: 10.1186 / cc7979.

- Bagshaw SM, Brophy PD, Cruz D, Ronco C. Balance de fluidos como biomarcador: impacto de la sobrecarga de fluidos en el resultado en pacientes críticos con lesión renal aguda. Cuidado crítico. 2008; 12 (4): 169. doi: 10.1186 / cc6948.

- Malbrain MLNG, Van Regenmortel N, Saugel B, et al. Principles of fluid management and stewardship in septic shock: it is time to consider the four D’s and the four phases of fluid therapy. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):66. Published 2018 May 22. doi:10.1186/s13613-018-0402-x

- Weil MH, Henning RJ. New concepts in the diagnosis and fluid treatment of circulatory shock. Thirteenth annual Becton, Dickinson and Company Oscar Schwidetsky Memorial Lecture. Anesth Analg. 1979;58(2):124–132. doi: 10.1213/00000539-197903000-00013.

- Monnet X, Teboul JL. Passive leg raising: five rules, not a drop of fluid! Crit Care. 2015;19:18. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0708-5.

- Jozwiak M, Depret F, Teboul JL, Alphonsine JE, Lai C, Richard C, Monnet X. Predicting fluid responsiveness in critically ill patients by using combined end-expiratory and end-inspiratory occlusions with echocardiography. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(11):e1131–e1138. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002704.

- Hoste EA, Maitland K, Brudney CS, et al. Four phases of intravenous fluid therapy: a conceptual model. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113(5):740–747. doi:10.1093/bja/aeu300

- Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, Peterson E, Tomlanovich M. Terapia temprana dirigida a objetivos en el tratamiento de sepsis severa y shock séptico. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345 (19): 1368-1377. doi: 10.1056 / NEJMoa010307.