Sepsis is defined as a systemic inflammatory response to infection. This scenario is encountered daily in all healthcare centres with a rate of 10 per 1,000 hospitalised patients.

This condition is of great importance as mortality is observed in 20% of sepsis cases and in 60-80% of patients with septic shock. Early diagnosis and prompt action are therefore vital.

The best way to analyse this condition and its treatment is through the analysis of clinical cases, so we have counted on Dr. Sergi Tormo Ferrándiz from the Intensive Care Medicine Department of the Hospital Universitari i Politècnic la Fe de València, who has shared the case of a patient in septic shock from the moment he enters the emergency room door until he is discharged from the ICU.

Emergencies

On this occasion, Dr. Tormo presents the case of a patient with the following profile:

- 40 years old

- Chronic alcoholic habit of more than 150 g ethanol per day.

- Obesity

- No other medical or surgical history of interest

This patient comes to the emergency department with abdominal pain radiating to the back accompanied by vomiting several hours after alcoholic transgression.

The first thing that strikes the ED staff is the general poor appearance of the patient, who presents with a tachycardia of 120 beats/minute, elevated tachypnoea and a blood pressure of 110/60 mmHg.

However, his oxygen saturation was good, thanks to a non-invasive mechanical ventilation device.

Once he was afebrile, conscious and oriented, the physical examination continued, with an intensely painful abdomen on palpation and diffuse signs of peritoneal irritation.

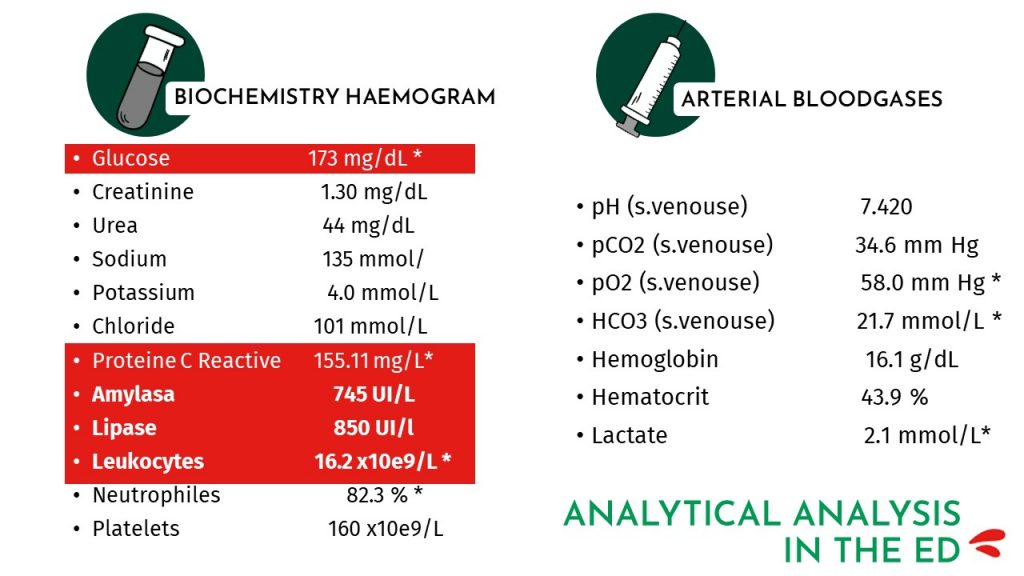

The blood test showed hyperglycemia of 173 mg/dL together with acute phase reactants with a very high C-reactive protein accompanied by leukocytosis.

There were also other biochemical alterations such as elevated amylase and lipase, which is a sign of acute pancreatitis.

Arterial blood gas analysis showed normal values, with a slightly elevated lactate level of 2.1 mmol/l.

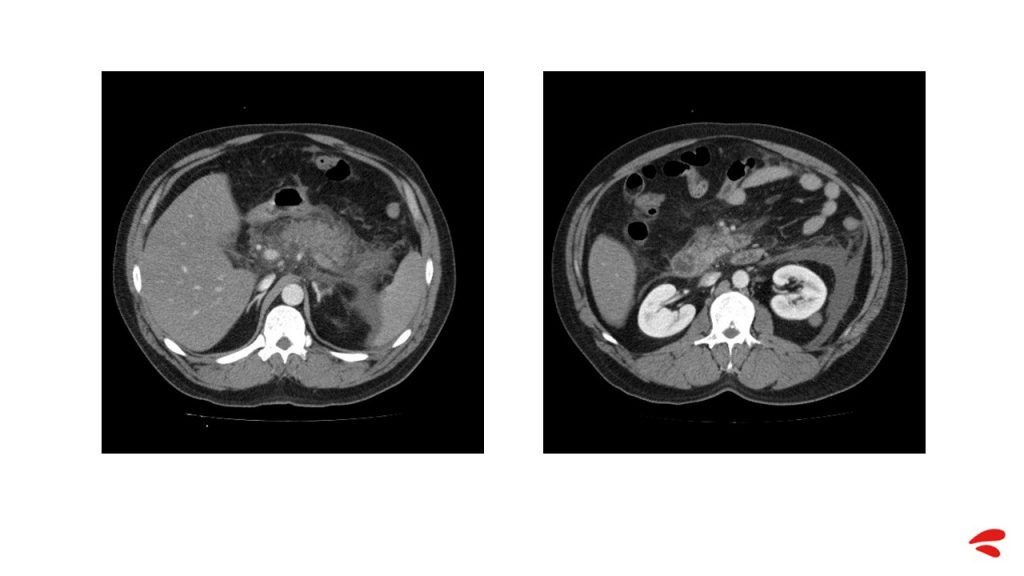

In view of these signs of peritoneal irritation, it was decided to perform an abdominal CT scan, which revealed acute necrotic pancreatitis, visible even without contrast infusion. A repletion defect in the superior mesenteric and splenic veins compatible with thrombosis was also visible, but no intra-abdominal collections were identified.

During the stay in the emergency room, the patient evolves unfavorably, his saturation falls despite the use of a non-mechanical CPAP system at 50%, he is intensely tachypneic and has a significant acral coldness and reticular libido.

In addition, the patient was oliguric after urinary catheterisation, so it was decided to administer 2 litres of crystalloids, but no improvement was observed.

All this, together with intense abdominal pain despite analgesia and hypotension, led to the decision to admit the patient to the ICU.

ICU

Situation on admission to the ICU

As no improvement was observed after the treatment administered in the emergency department, it was decided to transfer the patient to the ICU.

Once here, the professionals analyse the patient’s condition, who is in frank septic shock.

At this time the patient’s counts are as follows:

- Blood pressure: 70/45 mmHg.

- SatO2: 91% with non-mechanical CPAP device at 50%.

- Heart rate: 140 beats/min

- Temperature: 38.5°C

- Oliguria: 35 ml in the following 3 hours.

The patient underwent a new blood test in which procalcitonin (PCT) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were requested. The results showed an increase in both parameters, but they were not the only ones to have increased; leukocytes with neutrophilia and lactate also showed higher values.

Metabolic acidosis is also observed with bicarbonate of 15 mmol/l and pH 7.20.

First 6h

In a septic shock scenario, the ‘survive sepsis’ campaign recommends culture extraction and volume administration during the first hour for antibiotic administration, and this was done.

In addition, during these first six hours, parameters such as mean arterial pressure, saturation or diuresis should be monitored, so that in the event of a septic focus it is possible to act and try to control it.

If, despite the administration of volume during the first hour, the patient continues to be hypotensive, volume should continue to be administered, as volume is the only parameter that is indicated during the first 6 hours of resuscitation.

“It is recommended not to do this blindly. Do it guided by targets in response to this volume management.”

Returning to the case of our patient, we are dealing with a patient with abdominal septic shock, who also has significant respiratory failure and is starting renal failure.

With any patient, Dr. Tormo asks the following questions to guide his treatment:

- Is my patient going to respond to fluid administration?

- What liquids are we going to administer?

- How much?

- For how long?

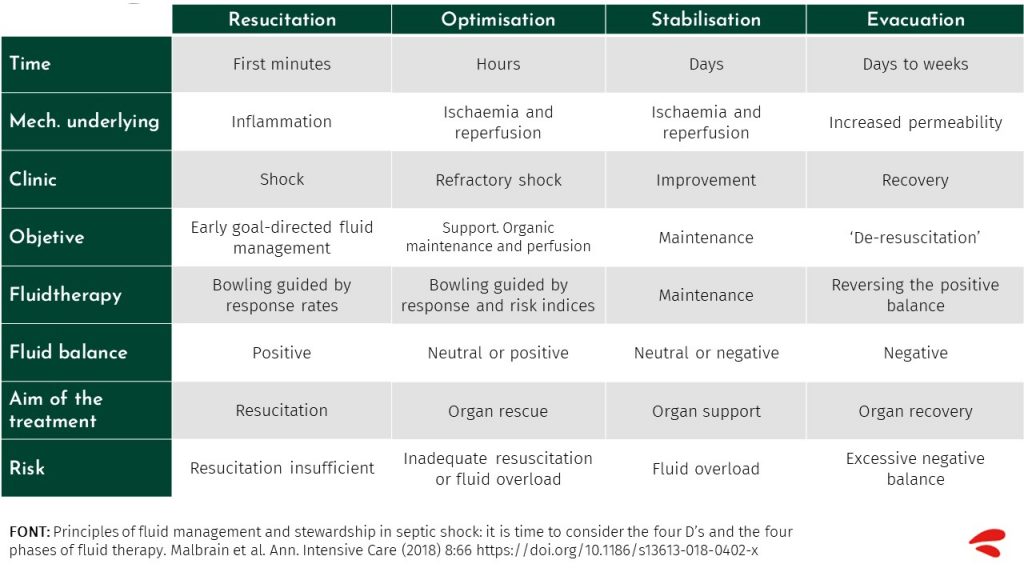

It is very important to analyse these issues and to administer the exact volume in each phase of resuscitation (ROSE Concept: Resuscitation, Optimisation, Stabilisation and Evacuation), as fluid overload could act negatively on different organs, causing different problems depending on the affected system.

What stage are we in with our patient?

To determine which phase we are in, we must analyse the previous treatment in the emergency department.

The patient has been administered 1500 ml of saline blindly and the patient is in volume refractory shock requiring the administration of vasopressors.

In addition, there are signs of organic ischemia and hypoperfusion. Therefore, we are in a situation where there is a high risk of insufficient fluid therapy or overload given the presence of respiratory failure.

We are therefore in the optimisation phase, where it is necessary to guide fluid therapy by response rates.

Optimisation phase

During these first hours in the ICU, corresponding to the optimisation phase, noradrenaline was administered and cannulated via radial intra-arterial and subclavian central venous lines, and hemodynamic monitoring was carried out using the P.R.A.M. method.

These were the parameters collected:

- BP: 70/40 mmHg

- CI: 3.8 lit/min/m2

- PPV: 22%.

- SVVS: 25%.

- Dp/dt max: 1.8

- PVC: 5 mmHg

- IRVS: 947 din-sec-m2/cm5

- SatVc: 82% SatVc: 82

Analysis of these results led them to continue guided volume management.

Which parameters to use to measure the fluid response?

For a goal-directed therapy the doctor presents different parameters that can help us to optimise the treatment.

- PPV/VVS

In this patient, pulse pressure variation and stroke volume variation could not be used because the patient was spontaneously breathing.

- Ultrasound

An ultrasound scan was attempted in which a lot of free abdominal fluid was observed with an acute abdomen, making it difficult to see the caval veins.

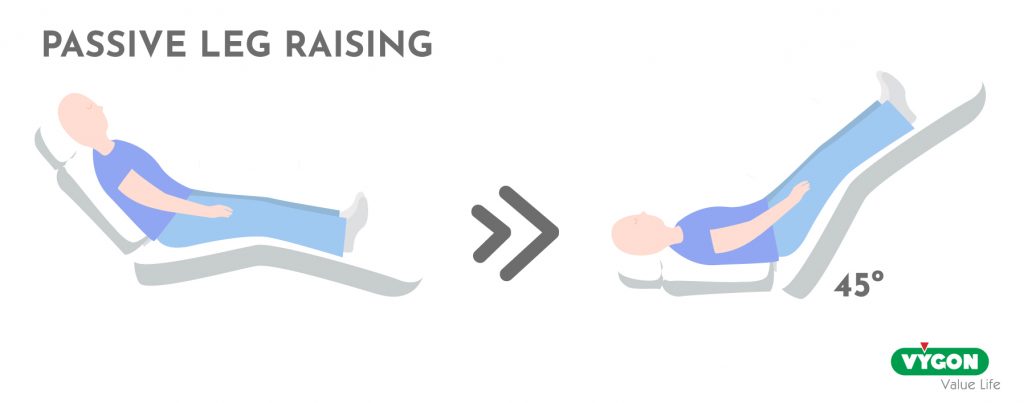

- Passive leg elevation test

The patient was severely tachypnoeic and had difficulty tolerating decubitus, so the passive leg raising test had to be discontinued.

- Mini fluid challenge and fluid challenge

As it was not possible to analyse the patient’s condition and response to the fluid using the above parameters, the mini fluid challenge was used.

Mini fluid challenge and fluid challenge

The mini fluid challenge test involves, under continuous monitoring of cardiac output, administering a bolus of 100 ml of saline over one minute and assessing whether the cardiac output increases above 6%.

On performing this test, the patient was observed to respond favourably and a bolus of 500ml was administered immediately. This procedure was continued until the patient stopped responding.

24 hours after admission to the ICU

A total of 1,500ml by volume of saline plus 300ml corresponding to the mini fluid challenge was administered.

Thus, the patient received 1,800ml of plasmacyte in the following 2 hours with partial improvement in blood pressure after the start of noradrenaline.

Suspecting septic shock, antibiotic treatment was started with meropenem administering 2 grams every 8 hours, but the patient worsened over the next 24 hours.

Although lactate levels had initially been normalised, he subsequently returned to higher values, accompanied by a fever that did not fall below 37.8ºC and intense neutrophilic leukocytosis.

In order to know more precisely what was happening in the patient’s body, intra-abdominal pressure was also monitored and showed elevated values at 24 mmHg with deterioration of renal function and an increase in creatinine.

Given the hemodynamic and respiratory situation, it was decided to intubate and connect the patient to mechanical ventilation.

Evolution at 72 hours

The evolution over the following three days was refractory septic shock with the need for noradrenaline in increasing doses, febrile peaks and progressive anemia.

The treatments that were considered were:

- Total parenteral nutrition

- Initiation of sedorelaxation

- The patient remained in anuria for the first few hours, so extrarenal clearance techniques were started with continuous venous hemofiltration.

- Maintenance of hemodynamic monitoring with echocardiography.

On the third day, amikacin and fluconazole were added to the antibiotic treatment with meropenem. After 72 hours, stabilisation was achieved with volume, noradrenaline, corticosteroids and sedation-relaxation.

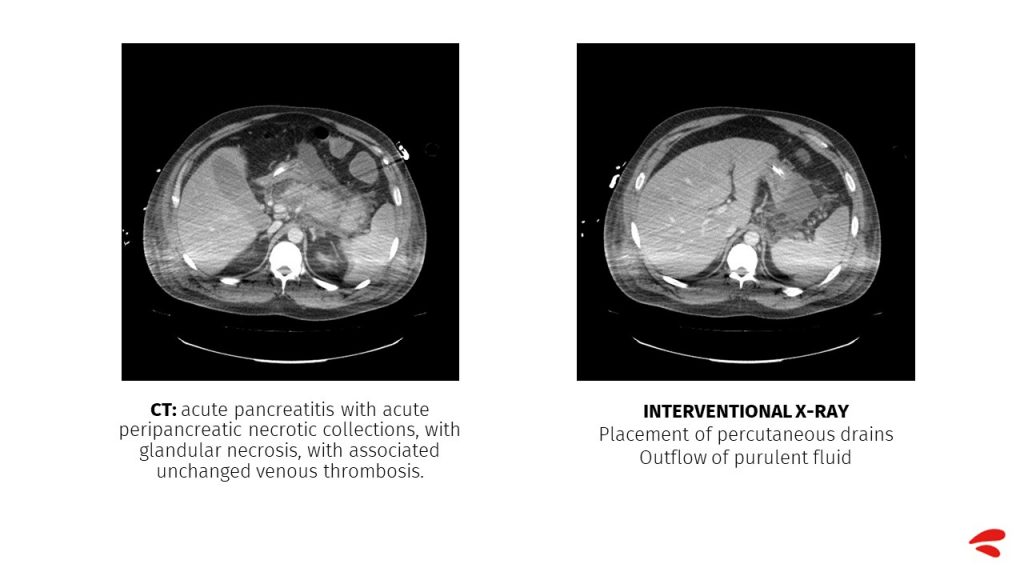

A repeat abdominal CT scan showed acute pancreatitis with acute peripancreatic necrotic collections, with glandular necrosis, and a previous venous thrombosis unchanged from the first test.

Day 4 of admission

When the patient returns on the fourth day of interventional surgery, he is again in shock accompanied by:

- Significant drop in blood pressure to 85/55

- Bacteremia

- Febrile peak of 39ºC

- Tachycardia of 125 beats/minute

- Intra-abdominal pressure controlled at 12 mmHg

In addition, monitoring using the P.R.A.M. method shows the following:

- Elevated cardiac index: 3.2 lit/min/m2

- Decreased vascular resistance index: 900

- Systolic volume variation: 22%.

- Pulse pressure change: 25%.

- cVcSat: 78

After analysing the data, especially the SVV and PPV, plasma volume expansion is performed, administering a total of 1,500ml of plasmalyte, in 500ml boluses.

SVV and PPV

During the following hours the patient continues to be monitored with special attention to Systolic Volume Variation (SVV) and Pulse Pressure Variation (PPV), as they reflect pressure changes in mechanically ventilated patients without cardiac arrhythmias.

These parameters were chosen because of their close relationship with volume response, as well as a strong correlation with the cardiac index.

The target value for these parameters would be close to 10% for PPV and 13% for SVV.

Day 8-14 in the ICU

Following volume administration, increased noradrenaline and adjustment of antibiotics, an improvement in the patient’s condition and normalisation of lactate was observed.

- The following actions were taken to improve the patient’s condition:

- Placement of a nasojejunal tube and initiation of enteral nutrition.

- Separation of klebsiella pneumoniae sensitive to the prescribed treatment in the abdominal fluid.

- Surveillance cultures in which meropenem-resistant pseudomonas aeruginosa was isolated.

- Upon observing new febrile peaks, treatment was changed from meropenem to ceftolozane – tazobactam.

In the days following the start of this treatment, the patient is stable and shows no new febrile peaks.

Day 15 in the ICU

Despite the great progress made during the past week, on day 15 the patient shows a worsening accompanied by new febrile peaks, shock and respiratory failure.

- New symptoms that the patient had not previously shown such as atrial fibrillation, which is attempted to cardiovert without success, so an amiodarone infusion is stopped and the heart rate is controlled.

- Intra-abdominal pressure remains stable at around 12 mmHg with a soft abdomen.

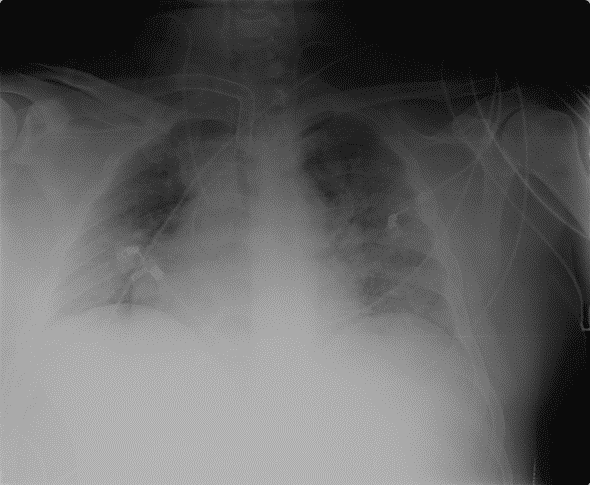

- Chest X-rays showed bilateral condensation. Suspicion of nosocomial pneumonia led to a change in antibiotic treatment and a CT scan was performed to rule out intra-abdominal complications.

This CT scan shows pancreatitis with pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosis but no new complications. What is seen is the splenic infarction, which was already visualised after the splenic vein thrombosis.

The diagnosis concluded with nosocomial pneumonia and sepsis of respiratory origin, arterial blood gas analysis was performed again and again revealed acidosis.

He again presented as hypotensive with the following constants:

- BP: 90/55 mmHg

- HR: 120 beats/min (Atrial fibrillation)

- SatO2: 92% (FiO2 of 0,5)

- CI: 3.3 lit/min/m2

- PPV: 35% VPP: 35% SVC: 27% SVC: 27% SVC: 27% SVC: 27

- SVVS: 27

On this occasion, of the parameters available to measure the response to fluids, and of which we have spoken previously, the passive leg raising test was chosen, as the others presented different risks.

Leg Lift Test

This test involves transfusion of 300 ml of blood from the legs to the heart by changing the patient from a semi-reclined position to a 45° leg elevation.

A good fluid response is considered to be present if a greater than 10% increase in stroke volume index is shown in the next minute.

The result in our patient was positive, so volume expansion was performed, and the patient tolerated a maximum of 1,000 ml of crystalloids, at which point he stopped responding and noradrenaline had to be increased.

The antibiotic was also changed to ceftazidime-avibactam, as there was an outbreak of a multidrug-resistant klebsiella that was subsequently isolated.

Last stage of admission

After this treatment an improvement was observed and on the 53rd day of stay in the ICU it was possible to disconnect the patient from mechanical ventilation, and he was transferred to the ward on the 62nd day after being decannulated.

At this time the patient is oriented, conscious, with a very good general appearance and tolerating enteral nutrition.

Conclusions

The following conclusions can be drawn from this case study:

- In cases of septic shock, initial fluid resuscitation is necessary.

- Antibiotics and an initial bolus of crystalloids should be administered within the first hour.

- If shock persists despite the volume administered, an intra-arterial line is cannulated and vasopressor therapy is initiated.

- Subsequent volume expansion should be monitored (cardiac output).

- Preload parameters PPV and SVV have a high sensitivity and specificity to guide fluid resuscitation.

- In spontaneous breathing or arrhythmias, the leg raise test and the fluid challenge or mini fluid challenge would be the methods of choice.

- Multiparametric monitoring with determination of CO, echocardiography and parameters assessing O2 consumption are recommended to better understand the patient’s condition and guide therapy.