This article about chest and neck veins is part of a series about the anatomy and physiology related to vascular access. To read the first part about arm veins, click here.

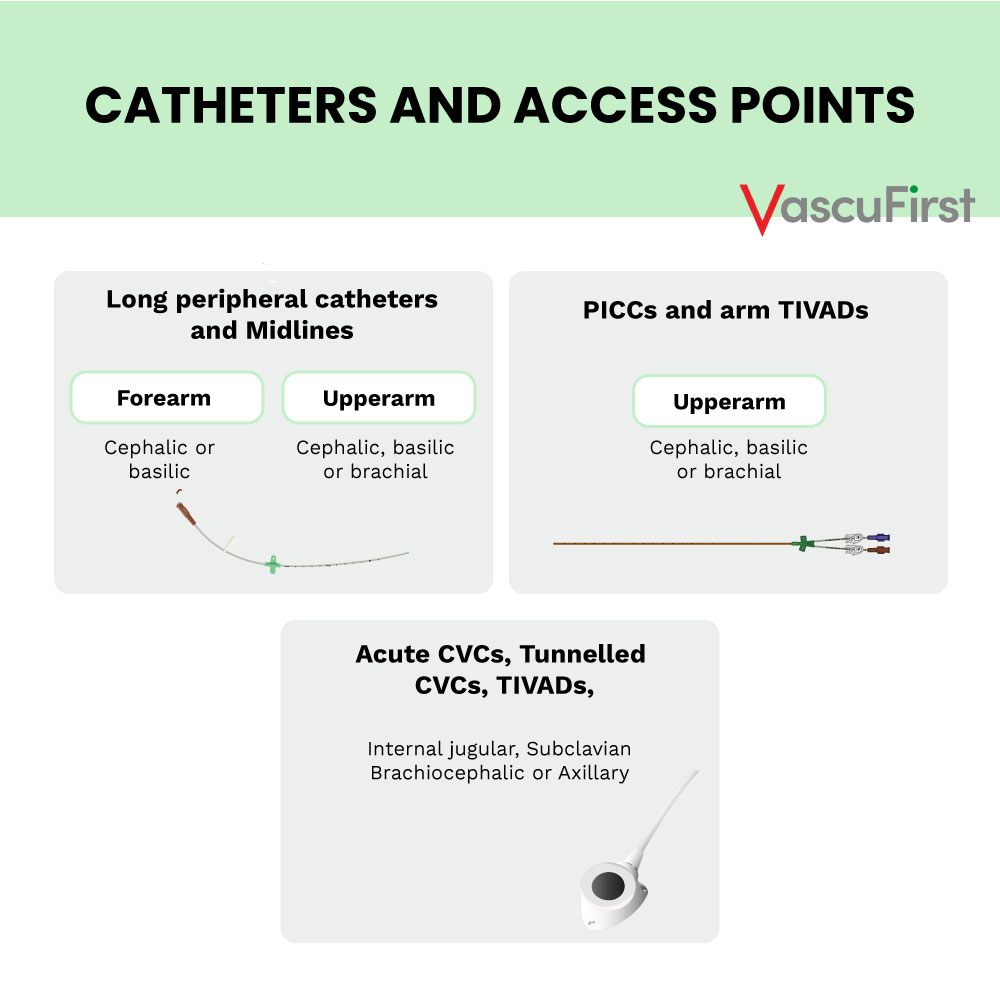

Chest and neck veins are often used for the insertion of acute central venous catheters (CVCs), totally implanted central catheters (TIVADs) and tunnelled central venous catheters (TCVCs).

Insertion sites for chest and neck veins include:

– Internal Jugular Vein (IJ)

– Subclavian Vein

– Brachio – cephalic vein (left and right innominate veins)

-

Internal jugular vein (IJV)

The IJV originates in the posterior part of the jugular foramen, under the posterior part of the floor of the tympanic cavity. The IJV is continuous with the sigmoid sinus. Its origin, however, is demarcated by a dilation called the superior bulb of IJV. The IJV passes through the jugular foramen along with the internal carotid artery. It lies posterior to the artery, with the glossopharyngeal, vagus, accessory and hypoglossal nerves passing between their adjoining surfaces. The IJV next traverses the carotid sheath. It descends in an almost vertical way down the neck. In the sheath, the IJV lies lateral to the common carotid artery and the vagus nerve. The IJV terminates posteriorly to the sternal end of the clavicle by merging with the ipsilateral subclavian vein and forming the brachiocephalic (innominate) vein.

The internal jugular vein access is popular for both acute central venous catheters (CVC), tunnelled central venous catheters (TCVC) and totally implanted vascular access devices (TIVAD).

Considerations

The right IJV offers a direct route to the superior vena cava (SVC). However, the left IJV takes a sharp turn to get to the SVC so often requires fluoroscopy to ensure safe placement. The carotid artery runs alongside the IJ so should also be visualised with ultrasound prior to puncture.

-

Subclavian Vein

The subclavian vein merges with the IJV on either side to form the brachiocephalic (innominate) veins. The subclavian vein starts when the axillary vein ends at the middle third of the clavicle. The subclavian vein is often difficult to visualise with ultrasound because its origin is posterior to the clavicle. Additionally, because the subclavian vein is underneath the clavicle it is difficult to compress if there is an inadvertent arterial puncture. Due to the proximity to the lung, this approach is associated with pneumothorax (Machat, 2019). This approach is also associated with pinch off syndrome which is the fracture of a catheter caused by the compression of the catheter between the clavicle and the first rib.

-

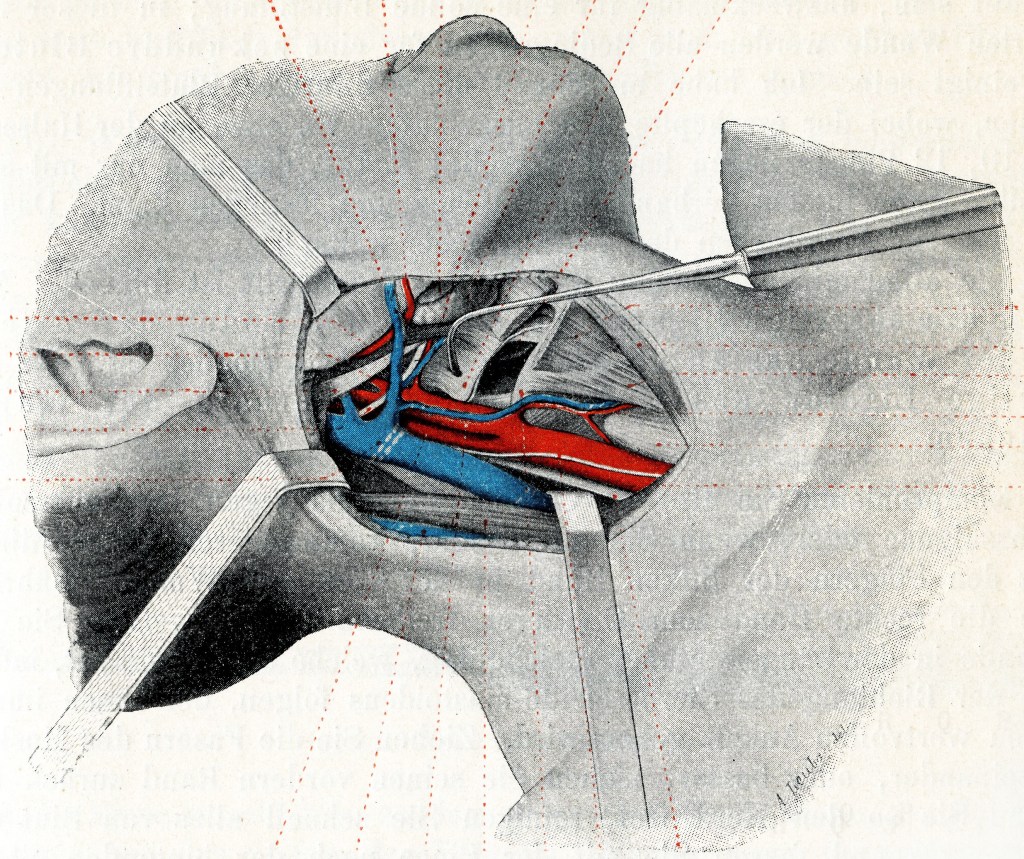

Axillary Vein

The axillary vein is a major vein in the upper body. It carries blood from the upper limb, armpit, and the upper side of the chest wall towards the heart. On each side of the body, it forms where the basilic and brachial veins join in the axilla. This is a space below the shoulder that allows arteries, veins, and nerves to pass. The course of the axillary vein is quite short as it moves towards the middle of the body. It becomes the subclavian vein at the border of the first rib. The axillary vein is a good access option as it is compressible with ultrasound and minimises the risk of pneumothorax associated with the subclavian approach. Also, arterial puncture could be controlled here if punctured inadvertently.

-

Brachiocephalic (innominate)

The brachiocephalic veins, also known as the innominate veins, are found in the thorax. They originate from the joining of the subclavian and the IJV. The left and right brachiocephalic veins meet to form the superior vena cava (SVC) on the right side of the chest. The Brachiocephalic (innominate) vein has become a popular access point for TCVC and TIVAD insertion (Sun et al. 2019). This is due to the use of ultrasound guidance.

-

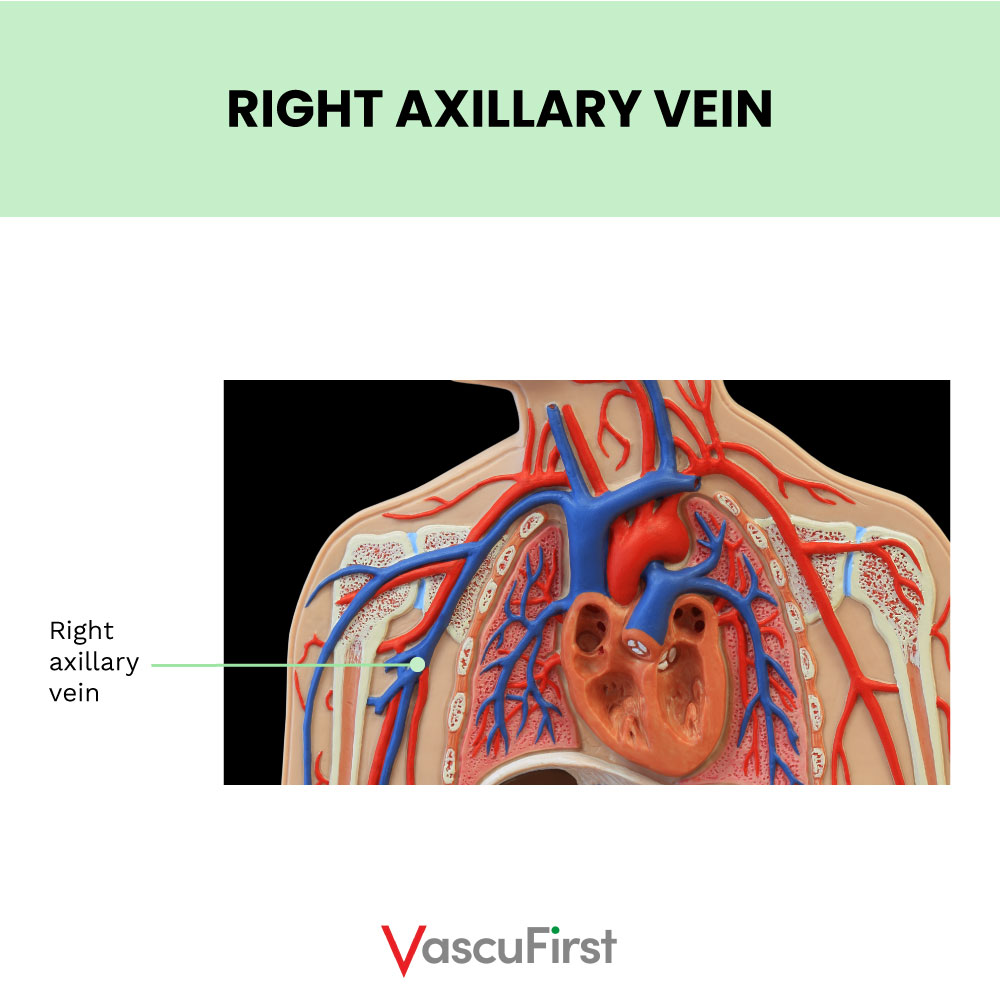

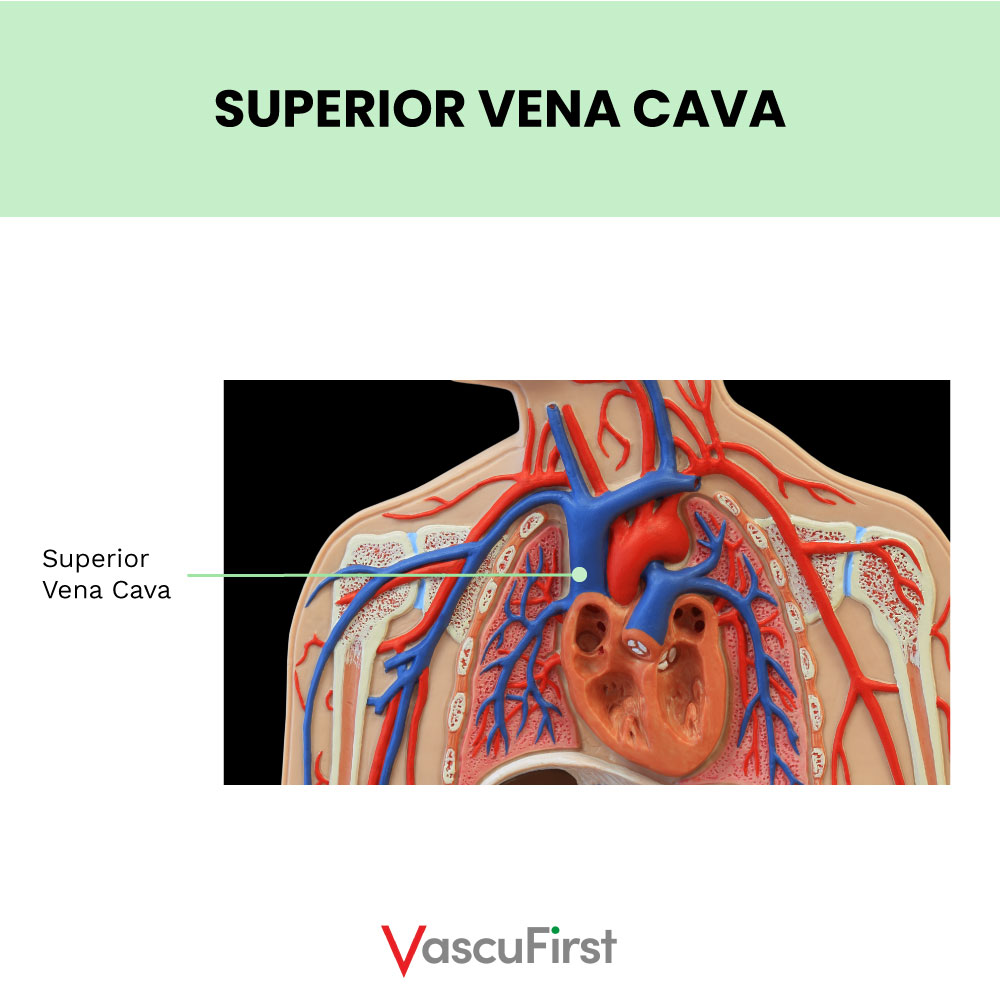

The Superior Vena Cava (SVC)

The SVC carries blood from the upper part of the body. It is formed from the joining of the two brachiocephalic veins behind the lower border of the first right costal cartilage.

The SVC is approximately 2cm wide and contains no valves. In adults it is around 7cm in length. It descends along a straight path and terminates in the upper right atrium.

A branch of the SVC is the azygos vein, which ascends on the right side in the posterior mediastinum, before arching forward to penetrate the posterior wall of the SVC at the level of the fourth thoracic vertebra. This junction is midway along the SVC and just over the pericardial reflection. Catheter tips can inadvertently lie in this junction or in the azygos vein with potentially adverse consequences (Harish, 2012).

-

Persistent Left Superior Vena Cava

This is a common normal variant (the incidence in the normal population is about 1 : 300). This variant is often found incidentally during Central Venous Catheter (CVC) placement and subsequent chest x – ray. It is a variant that makes the insertion of CVCs problematic and one that vascular access specialists should be aware of.

-

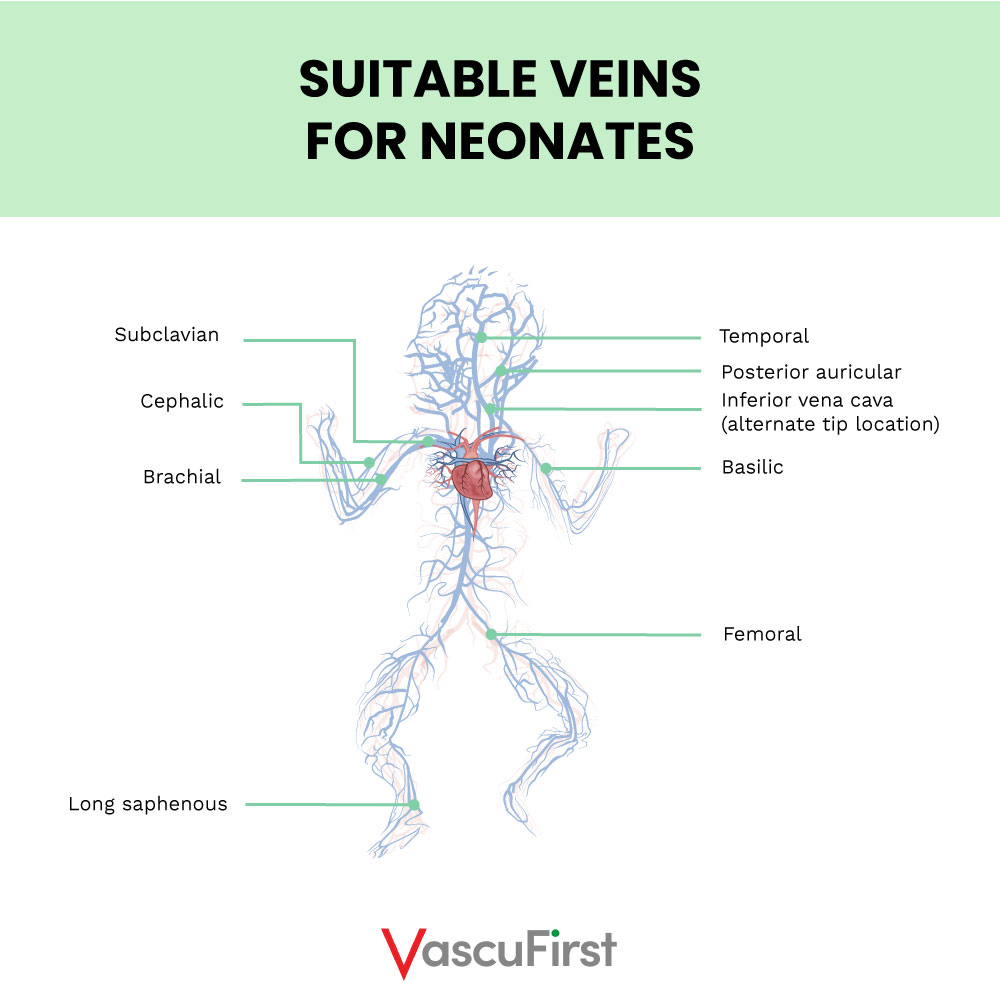

Arms, chest and neck veins access in neonates

Vein selection in neonates includes scalp veins. The suitable veins are demonstrated in the image below:

-

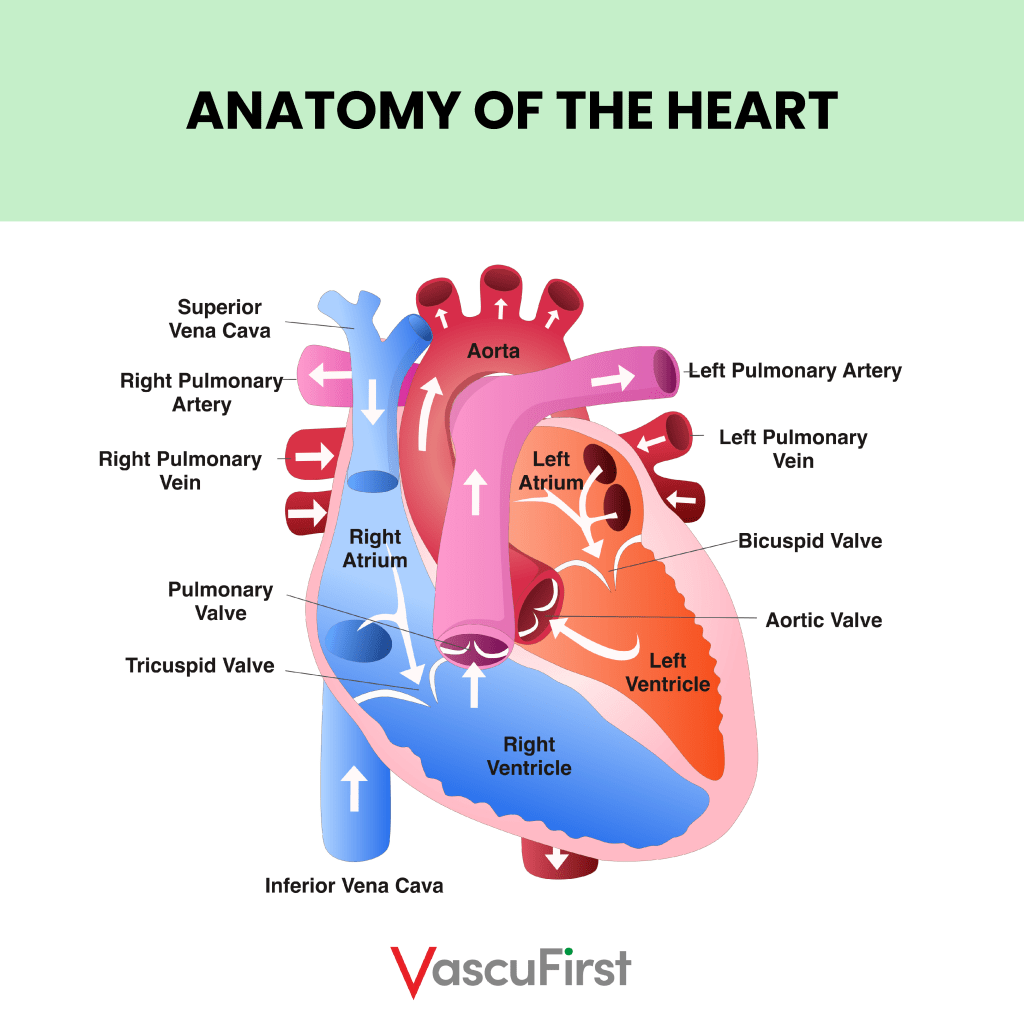

Central Venous Catheter Tip Position

A central venous catheter is defined as one that terminates in one of the large central veins of the body: SVC or upper right atrium. (Fletcher and Bodenham, 2000).

A central vein is one that is close to the heart (the centre of circulation). Central veins where CVC tips terminate are the superior vena cava (SVC), Inferior vena cava (IVC) or right atrium. The vessels that are near the heart are larger and therefore they have a greater blood flow. This greater vessel width helps to reduce damage to the intima from sclerosant infusions or from the catheter itself.

CONCLUSION

Vessel health and preservation (VHP) should always be considered. This includes consideration of which vein to use for device placement. The most appropriate vein and insertion site should be selected to best accommodate the device being placed. Both vein and insertion site should be selected with the patient and healthcare team and based on the projected treatment plan. You should always choose the most appropriate site that is likely to last the full length of prescribed therapy.

Although the practitioner should use their professional judgement to select the most appropriate vein for cannulation, this decision should be based on patient history and anatomy and the availability of ultrasound guidance and fluoroscopy.