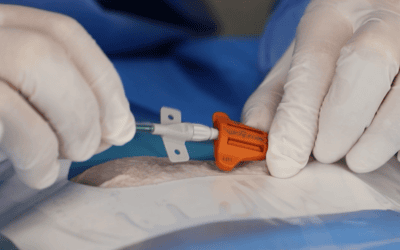

Research is showing that upwards of 90% of hospitalized patients receive a Peripheral IV (PIV) during their stay, resulting in hundreds of millions of PIV catheters being sold throughout the world, with over 300 million being sold in the United States alone. Unfortunately, research has shown that failures in these catheters can be as high as 63%(1), directly resulting in multiple catheters and repeated venipunctures in order to complete therapy. Although there is a myriad of reasons for these failures, it is quite often that vein irritation is the cause for removal(2). However, despite the risk of complications and the high rate of failures, vascular access devices (VADs) are a necessity for patients as they receive life-saving medications through them.

Due to the necessity of VADs, clinicians and researches are looking to improve practice and have a direct impact on the quality of care that they provide to patients. This has led many of us towards looking at PIVs in a different way and wondering if we need to think about them differently. Therefore, many in the vascular access industry and those practicing within it have begun conversations around two topics that focus around the idea of “Reducing Venous Depletion” and “Vein Preservation”.

The first topic of extending the life of the catheter and increasing dwell days is being discussed and studied extensively and to great effect.

The second topic is a growing conversation in United States and revolves around the damage that power injection and power flushing could cause to the vein. With the advances of technology, clinicians like the Australian AVATAR Group(3) is showing the damage caused inside the vein during flushing at 1 and 2 mL/sec (imagine what happens with a power injection of 5mL/sec). They have been able to see “real-time” images and video of what is going on inside the veins during these turbulent injections. These images confirm that there are two things happening:

1) The catheter “whips” back and forth causing trauma to the endothelium layer of the vein.

2) The force of the injection, by itself, is causing sheering of that same endothelium layer.

What no one is denying within these discussions is the need for both power injection and power flushing.

One is needed for proper diagnosis of various disease states, while the other is needed for catheter patency. However, the conversations are bringing to light questions directly related to best patient care:

One is needed for proper diagnosis of various disease states, while the other is needed for catheter patency. However, the conversations are bringing to light questions directly related to best patient care:

1) What is the correct frequency of power flushes for line patency and can we be over doing it with that frequency?

2) Does every device placed into a patient need to be power injectable?

While there is a lot of research that needs to be done on both topics, spending a few minutes discussing the second question, leads us many subsequent questions, facilitating the need for an expansive study and more conversations within the industry. For years there has been a push to have every device within the hospital have the capability for power injection. However, as acuity levels of patients increase and the frequency of their visits to in and out-patient clinics/hospitals for treatments increase, we see a decrease in a patients’ vasculature and a need to consider how to best preserve patients immediate and future vascular access needs.

As we look at power injection and our ability to answer the question of, “Does every device placed into a patient need to be power injectable?” there are several questions that have arisen in conversations with clinicians across a variety of disciplines:

a. How long are our peripheral power injectable devices providing blood return?

b. How many patients have a power injectable device get a power injection in the first device that you place?

c. Do you know what happens to the device after it is power injected into? And, how long does the device lasts after it is power injected through?

These questions are what we need to consider and, in doing so, decide if there is a better option to extend the life of catheters needed for therapy while preserving your patients’ precious veins.

Could it be that the goals of increasing the length of dwell of a catheter and the needs of Power Injectable procedures are not fully compatible?

And, therefore, should we be considering a line dedicated to IV therapy and a line dedicated for a procedure that is removed once the procedure is done, allowing the vein to recover from the damage being cause to it instead of continued use causing more irritation, infiltration and, ultimately, damage?

If we think about this as two separate goals, we might be able to save veins, as they are not renewable resources.

1. Helm, Robert E, et al. “Accepted but Unacceptable: Peripheral IV Catheter Failure.” Journal of Infusion Nursing, vol. 38, no. 3, 2015, pp. 189–203.

2. Rickard, C. et al Routine versus clinically indicated replacement of peripheral intravenous catheters: a randomised controlled equivalence trial. The Lancet 2012 vol 380; 1066-1074.

0 comentarios