The proportion of patients who have a central venous catheter inserted has increased over the years, so much so that 78% of patients admitted to intensive care units (ICU) in Europe have a CVC inserted.7

However, central venous catheter (CVC) placement has associated complication rates of approximately 15%.3

Among the most important risks we encounter in central venous cannulation are7:

- Infection.7

- Pneumothorax.7

- Hemothorax.7

- Gas embolism.7

- Local hematoma.7

- Thrombosis.7

- Central venous catheter-related bacteremia (CVCB).7

One of the most prominent complications associated with the use of central venous catheters is bacteremia2, which occurs in 1-15% of CVCs7. There are different maneuvers that can help us to reduce its incidence, such as the implementation of the Bacteremia Zero project or the use of antimicrobial catheters.

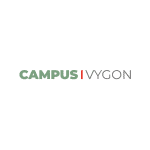

HOW TO AVOID INFECTION RELATED TO THE USE OF CENTRAL VENOUS CATHETERS (CVC)?

Catheter-related infections result in increased mortality, morbidity and costs.2

Due to the importance of this problem, in 2009 the Quality Agency of the Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs (MSC), in collaboration with the World Alliance for Patient Safety of the World Health Organization (WHO), launched the Bacteremia Zero project.

In addition to putting into practice the points collected by the Bacteremia Zero project, the choice of catheter can also have a great implication in avoiding different complications. According to different studies, the use of antimicrobial central venous catheters (CVC) reduces the rate of infection at the insertion site.

We can find different substances in the body of the catheter that can help us to reduce these complications, among which we find silver ions and rifampicin and miconazole.

Silver ions or rifampicin and miconazole, which one to choose?

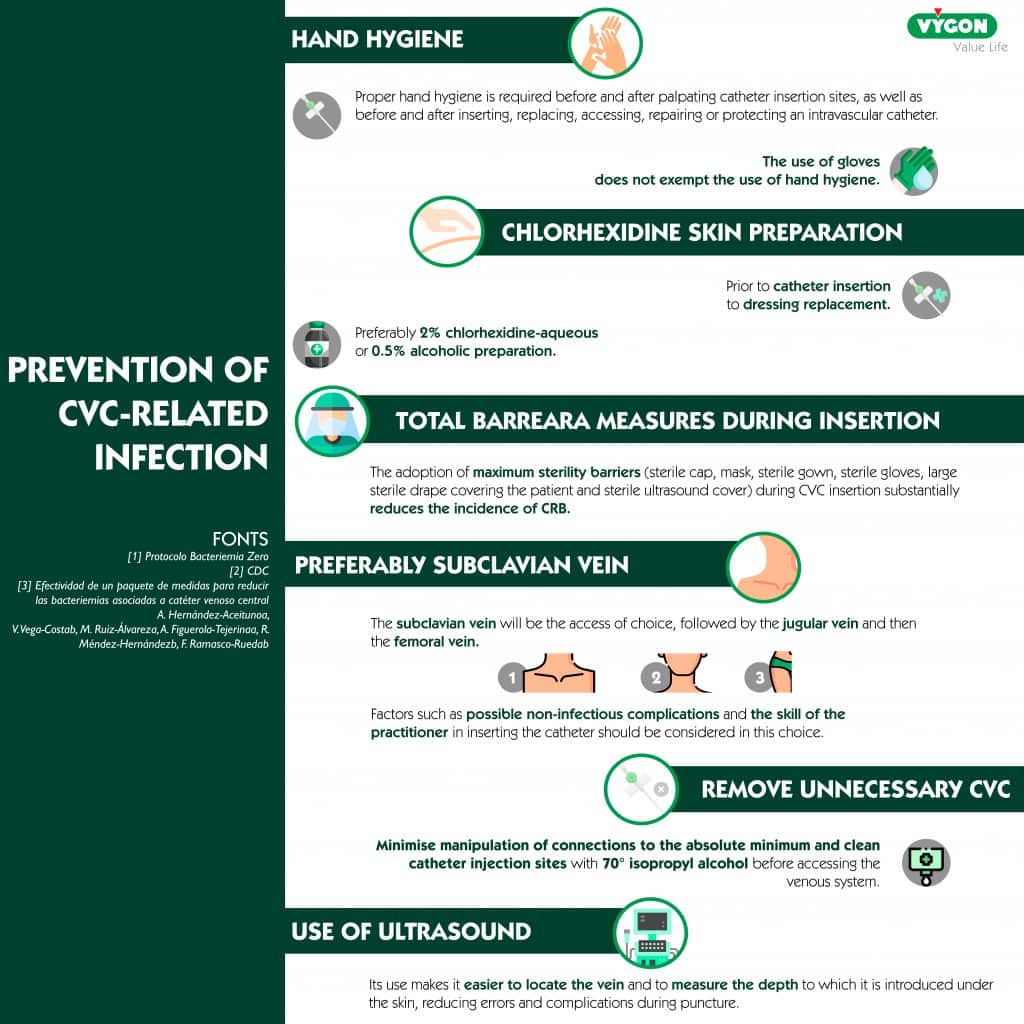

Silver ions, rifampicin and miconazole are all substances that can be found in catheters and have the same purpose: to reduce the incidence of catheter-related infection. So… Which one to use?

The use of one or the other will depend on the time the catheter is expected to remain implanted. In catheters that incorporate silver ions in their material, the average antimicrobial duration is about 3 to 4 days, whereas catheters with rifampicin and miconazole have a longer antimicrobial activity with a half-life of up to 21 days.4

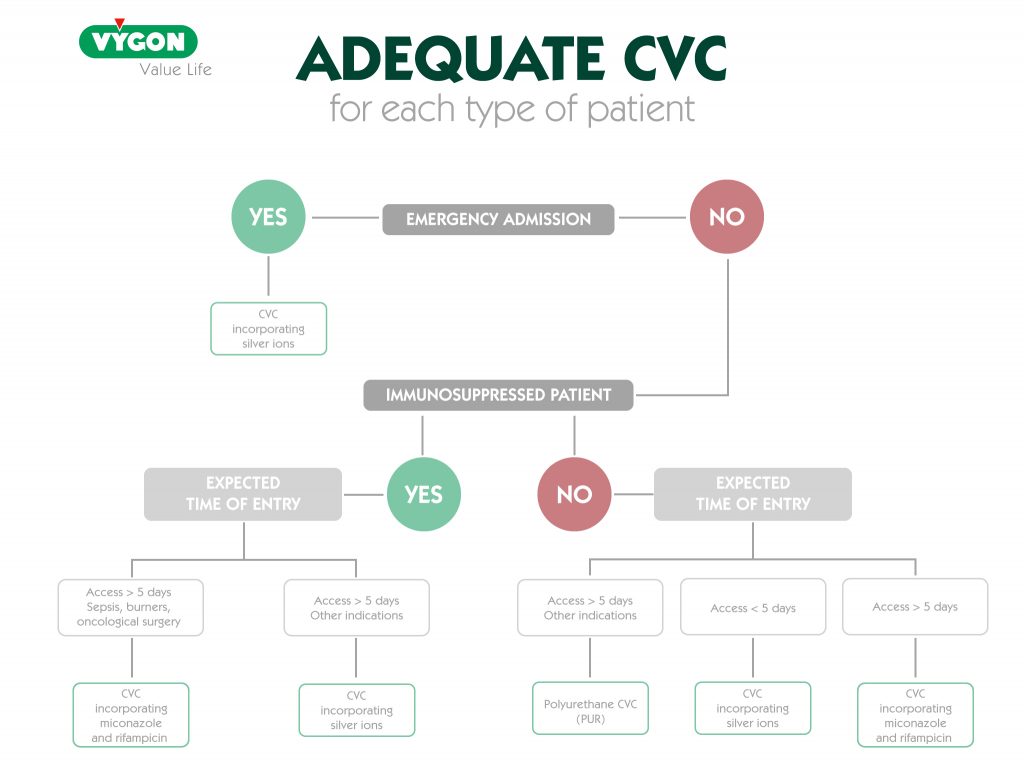

PROPERTIES OF RIFAMPICIN AND MICONAZOLE

Rifampicin and miconazole are two active substances that can be found in some central venous catheters. The combination of these two substances reduces possible complications related to catheter infection.

While rifampicin is a bactericidal antibiotic, miconazole is an imidazole derivative used in medicine as an antifungal.

MICONAZOLE

- Synthetic antifungal

- Broad spectrum antimicrobial activity

- Low toxicity

- Mechanical action: inhibition of peroxidases, preventing peroxide accumulation inside the cell, which would result in cell death

RIFAMPICIN

- Bactericidal antibiotic

- High efficacy against fast growing and resting bacteria in the biofilm such as Gram+ and – microorganisms.

- Mechanical action: inhibits RNA synthesis

Among the antimicrobial central venous catheters that incorporate these substances, we find those that are impregnated with them, and which release the molecules from the first moment and those that incorporate them in their composition, being released on contact with the blood, which is advantageous against infection.

As we have mentioned, rifampicin and miconazole can help reduce the incidence of complications, however, as with any medical device, catheters incorporating these two substances are not the first choice in all patients, but are recommended for a specific group.

TARGET

Rifampicin and miconazole catheters are used in critically ill patients when their stay is expected to be prolonged, since their antimicrobial activity is up to 21 days.4

Therefore, when opting for these catheters, we must take into account the estimated duration of treatment, as well as the probability of infection at the insertion site. Taking this into account, catheters with rifampicin and miconazole would be mainly intended for the following groups of patients:

- Immunosuppressed

- Burn victims

- Oncology

BENEFITS OF USING CENTRAL VENOUS CATHETERS WITH RIFAMPICIN AND MICONAZOLE

REDUCTION OF CATHETER-ASSOCIATED COLONIZATION, LOCAL INFECTION AND BLOODSTREAM INFECTION

Central venous catheters with rifampicin and miconazole prevent catheter-associated colonization, local infection and bloodstream infection. This is because the combination of both substances leads to protection against broad-spectrum microorganisms such as Staphylococcus, Enterobacterial and Candida.

FEMORAL AND JUGULAR ACCESS

The 2002 CDC guidelines recommend, whenever possible, opting for subclavian access, rather than femoral or jugular vein, in order to minimize the risk of infection.1,6

Since a large number of studies and scientific societies point to a lower rate of catheter tip colonization in the subclavian vein than in the femoral and jugular veins7.

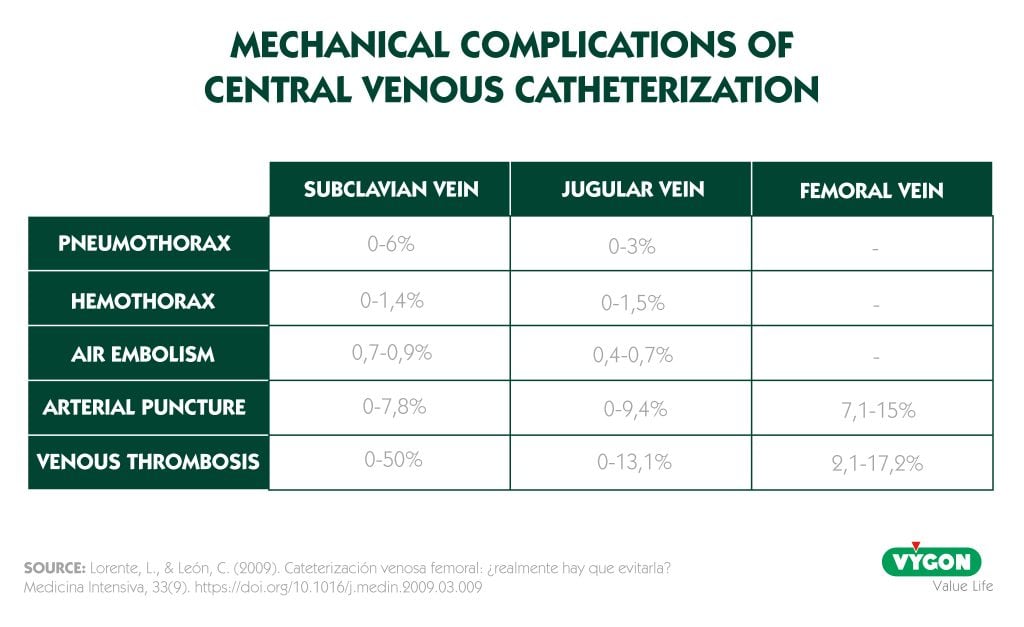

However, this is not always possible and, as we have seen, there are many other risks related to the insertion of central venous catheters. In addition, it should be taken into account that the abuse of the subclavian vein and the disuse of the femoral vein could lead to a decrease in the incidence of bacteremia, but an increase in the rate of mechanical complications such as pneumothorax or hemothorax.7

As can be seen in the table, the incidence of arterial puncture is higher with the femoral approach, but the risk of thrombosis is lower than with the subclavian approach, and as is logical, in the femoral approach there is no risk of pneumothorax, hemothorax or gas embolism.7

In addition, studies have shown that it is possible to reduce bacteremia in femoral and jugular accesses, the key being antimicrobial catheters.

Catheters with rifampicin and miconazole in femoral and jugular access

It has been demonstrated that the use of catheters with rifampicin and miconazole reduces bacteremia, as well as the incidence of catheter-related sepsis in femoral or jugular locations, presenting incidences of bacteremia equal to subclavian access.1

The choice of central venous access requires consideration of many variables and risks that each location may present, but when subclavian access is not possible, having antimicrobial catheters available allows the choice of jugular and femoral accesses to avoid increasing the risk of catheter-related bacteremia.

It is also important to take into account the length of the catheter and use the size that best suits each patient. In this way the free portion of the catheter will be smaller and the chances of infection will be reduced. Having a wide range of CVC sizes helps to make the best choice for each patient.

COST REDUCTION

Central venous catheter-related bacteremia (CVCB) increases morbidity and mortality and health care costs. The increase in costs is due to the need for antimicrobial treatment, complementary diagnostic tests and prolonged hospital stay.7

Thanks to the use of antimicrobial catheters, we are able to reduce the rates of catheter-related bacteremia and, therefore, also reduce costs.1,7

Antimicrobial catheters such as those incorporating rifampicin and miconazole can be of great benefit in patients at higher risk of developing infectious complications such as in femoral vein cannulation, immunocompromised patients or alterations in skin integrity.7

In order to increase patient safety and reduce costs, when selecting the catheter and central venous access, we should take into account all possible complications, both infectious and mechanical. And, when the catheter is expected to remain in place for long periods of time or the cannulation is to be performed in the jugular or femoral vein, we should consider the convenience of placing antimicrobial venous catheters that will provide greater safety against infection.7

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Lorente, L., Lecuona, M., Ramos, M., Jiménez, A., Mora, M., & Sierra, A. (2008). The Use of Rifampicin‐Miconazole–Impregnated Catheters Reduces the Incidence of Femoral and Jugular Catheter‐Related Bacteremia. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 47(9). https://doi.org/10.1086/592253

- Lorente L. (2016). Antimicrobial-impregnated catheters for the prevention of catheter-related bloodstream infections. World journal of critical care medicine, 5(2), 137–142. https://doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v5.i2.137

- Taylor, R. W., & Palagiri, A. V. (2007). Central venous catheterization. Critical Care Medicine, 35(5). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ccm.0000260241.80346.1b

- Michael Schierholz, J., Nagelschmidt, K., Nagelschmidt, M., Lefering, R., Yücel, N., Beuth, J. (2010) Antimicrobial Central Venous Catheters in Oncology: Efficacy of a Rifampicin–Miconazole-releasing Catheter

- Rump, A., Güttler, K., König, D., Yücel, N., Korenkov, M., & Schierholz, J. (2003). Pharmacokinetics of the antimicrobial agents rifampicin and miconazole released from a loaded central venous catheter. Journal of Hospital Infection, 53(2). https://doi.org/10.1053/jhin.2002.1358

- Hernández-Aceituno, A., Vega-Costa, V., Ruiz-Álvarez, M., Figuerola-Tejerina, A., Méndez-Hernández, R., & Ramasco-Rueda, F. (2020). Efectividad de un paquete de medidas para reducir las bacteriemias asociadas a catéter venoso central. Revista Española de Anestesiología y Reanimación, 67(5), 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redar.2019.11.014

- Lorente, L., & León, C. (2009). Cateterización venosa femoral: ¿realmente hay que evitarla? Medicina Intensiva, 33(9). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medin.2009.03.009