To refresh your memory and read the first part of the series about the key principles of PICCs, you can click here.

The use of PICCs has increased in recent years and can now be found in many specialties and in both hospital and out of hospital settings. Despite being devices that are beneficial to patient care, they are associated with potential complications. Such complications include: infection, occlusion, thrombosis, catheter migration, catheter fracture. To reduce complications and patient harm, it is important that clinicians know how to manage these devices safely. This article will focus on best practice in PICC use.

INFECTION PREVENTION AND CONTROL

PICCs provide a portal of entry for microorganisms which incurs a high risk of infectious complications. The frequency of handling and manipulation of these devices by various healthcare workers over their dwell time increases the risk of infection. Therefore, the importance of effective asepsis during every manipulation cannot be over emphasised.

Hand hygiene

Hand hygiene is a general term referring to any action of hand cleansing. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), most healthcare associated infections (HAI) are preventable through good hand hygiene practices. This involves cleaning hands at the correct times and in the correct way.

The WHO steps in hand hygiene are:

- Wet hands and apply enough liquid soap to create a good lather

- Rub hands palm to palm in circular motions

- Rub the back of hands

- Interlink fingers

- Cup fingers

- Clean the thumbs

- Rub palms with fingers

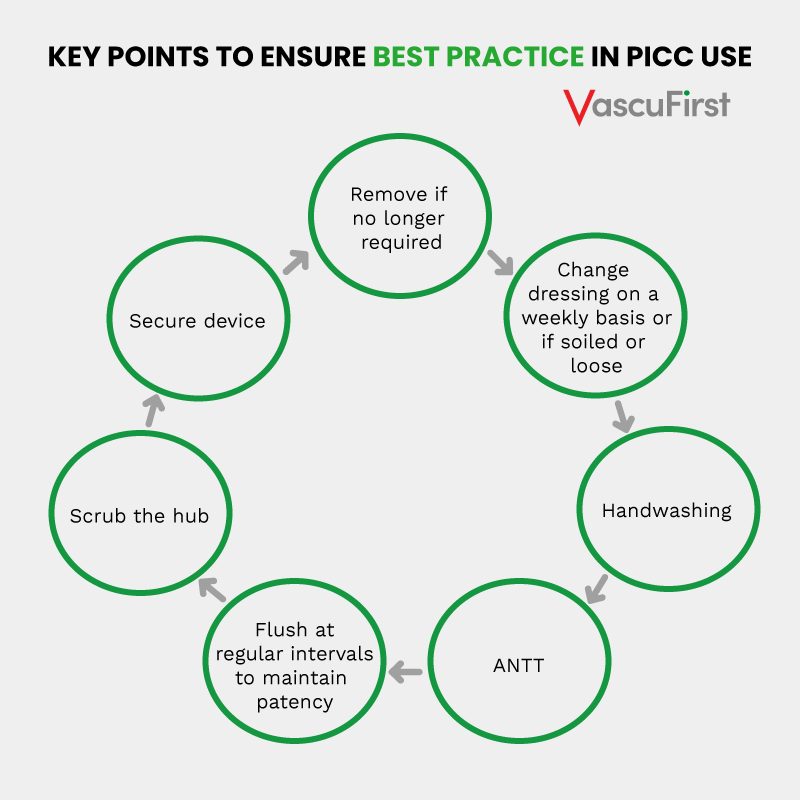

When handling vascular access devices, these steps and moments are vital. The other strategy used to reduce the risk of infections in PICCs is the use of an aseptic non-touch technique (ANTT) (Clare and Rowley, 2018).

Aseptic non-touch technique (ANTT®)

Aseptic non touch technique is a common but critical infection prevention strategy in healthcare. Aseptic technique involves a set of infection prevention actions targeted at protecting patients from infections associated with pathogenic microorganism transmission. ANTT® is designed as a practice framework for all invasive procedures including the maintenance of invasive devices. ANTT® is designed to define and teach a standard competency-based aseptic technique to healthcare workers (HCW). ANTT® is a unique, effective aseptic technique which aims to prevent the introduction of microorganisms into susceptible body sites (Rowley, 2001).

Fundamental to ANTT® is the concept of Key – Part and Key – Site Protection to maintain an aseptic procedure (Rowley and Clare, 2021).

Key – Parts include vascular devices such as PICCs. If these become contaminated, they provide a direct route for the transmission of harmful microorganisms into patients.

Key – Sites relate to areas of skin penetration providing a direct route of the transmission of pathogens into the patient. These include PICC exit sites.

Key – Part and Key – Sites must be kept aseptic at all times during PICC C&M procedures. This is achieved with the use of basic infective precautions such as hand washing and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE). In addition, the equipment used must be sterilised and aseptic fields maintained. The use of ANTT® will help to ensure asepsis during care and maintenance procedures.

There are three different types of aseptic fields that can be used during PICC C&M procedures:

Critical Aseptic Field: all equipment handled as Key – Parts. Sterile gloves used.

General Aseptic Field: a decontaminated and disinfected surface such as plastic procedure trays or dressing trollies are used. Use of micro critical fields. Non sterile gloves and non-touch technique (NTT) are used.

Micro Critical Aseptic Field (MCAF): these are used to protect Key – Parts individually (sterile caps and insides of recently opened sterile equipment packaging).

ANTT® can be either surgical or standard. Surgical ANTT® involves the clinician adopting a high level of precaution. This means performing a surgical scrub and donning sterile gloves, gown, hat and mask. The aim of surgical ANTT® is to eliminate all microorganisms. Whereas, standard ANTT® can be performed without this level of PPE whilst ensuring the procedure performed is clean and the number of microorganisms reduced. Either a surgical or standard ANTT® can be used when accessing PICCs or when doing C&M regimes.

Standard ANTT® should be used for PICC C&M procedures as they are usually of a short duration and involves negligible numbers of small Key-Parts that can be easily protected by using a non-touch techniques or by using individual Micro Critical Aseptic Fields.

The next section will discuss the main aspects of PICC C&M. These include: Skin antisepsis, hub care, catheter stabilisation / dressing and flushing.

Care and Maintenance (C&M)

Once a PICC has been inserted, it is important that the device is maintained and cared for so that complications are minimised or ideally prevented. The C&M regime for PICC includes dressing and flushing. This is typically performed on a weekly basis. These are done to prevent infection and occlusion which are two of the most common complications of PICCs.

Skin antisepsis

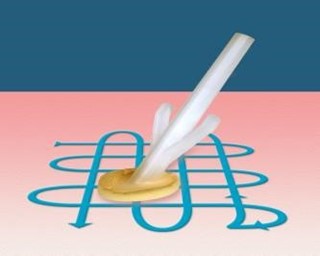

At every dressing change, the skin should be cleaned prior to replacing the stabilisation device and new dressing. Chlorhexidine 2% in 7% alcohol should be used to clean the skin (Loveday, 2014; Gorski, 2021). Skin should be cleaned for thirty seconds using a crosshatch (back and forth) technique.

This allows cleaning deeply down the skin layers. It is important to allow the skin to air dry naturally. This will ensure full effect of the antiseptic.

Needle Free Device (NFD) use and care

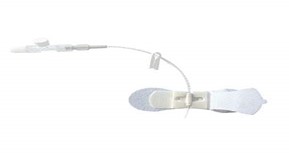

NFDs should be attached to the ends of PICCs. The purposes of NFDs are to maintain a closed system, reduce the risk of needle injuries and blood spillages. An additional aim is to improve clinician outcomes by reducing common complications of PICCs such as infection and catheter occlusion. NFD can be negative, positive or neutral fluid displacement. It is important to know what NFDs are used in your institution as this will affect the clamping sequence (Kelly, Kirkham and Jones, 2017).

The effective disinfection of NFD is crucial as they come into contact with microorganisms from both the patient and the environment while the device is not in use. Most recent evidence suggests that an adequate cleansing time with the use of alcohol and chlorhexidine is required to ensure effective cleansing. NFD can be cleaned either actively (scrubbing the hub), or passively. Passive cleaning involves the use of a hub cap impregnated with alcohol. These remain on the hub of the PICC while it is not in use.

Active NFD disinfection

Passive NFD disinfection

As guidance still fluctuates, always be guided by local policy on disinfectant and timings. NFDs are typically changed every seven days. Always refer to the information for use (IFU) if unsure.

PICC Stabilisation

The stabilisation of PICCs is vital if movement of the device is to be avoided. Constant rubbing of devices against the delicate vein intima can lead to mechanical phlebitis and lead to catheter failure. There are a variety of methods that can be used for PICC stabilisation. These include:

- Suturing

- Integrated securement devices

- Adhesive securement devices

- Subcutaneous securement devices

- Tissue adhesive

We should avoid suturing PICC onto the skin as this poses a risk of both needle stick injury, skin injury and infection (Barton, 2020).

Adhesive securement devices require changing every seven days or more frequently if soiled or loose.

Subcutaneous securement devices are anchored under the skin. These can remain in place for the dwell time of the device.

Tissue adhesive use is a novel approach to PICC securement so there is minimal evidence to guide best practice (Corley et., al. 2017; Nicholson and Hill, 2019).

PICC Dressing

Dressings should be transparent to allow visual inspection of the site, they should be self-adhesive, provide stability thus reducing the risk of vein intima trauma, phlebitis and contamination. The dressing should be semi-permeable to protect the site from bacteria and liquid while still allowing the skin to ‘breathe’ (NICE, 2003). Examples of suitable dressing are, Tegaderm or IV3000. The dressing should be changed weekly or more often if loose or soiled (Gorski, 2021).

Catheter clearance

Flushing is crucial to maintain catheter patency and function. Ineffective flushing can cause catheter malfunction and result in associated complications such as occlusion, thrombosis and infection, which can increase patient morbidity and mortality (Baskin et al. 2012). Consequences of inadequate flushing could include negative patient outcome and experience, treatment delays, costly thrombolytic therapy, antimicrobial therapy, device removal and reinsertion, increased hospital stay and organisational costs (Mitchell et al. 2009). PICCs should be flushed before and after use. If not in use, they should be flushed on a weekly basis (Denton, 2016, Gorski, 2021).

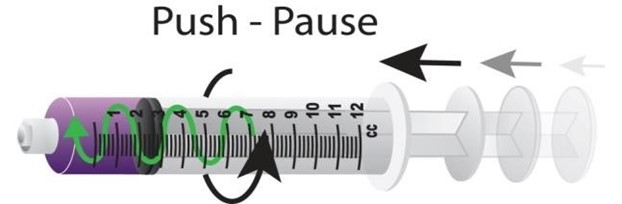

Catheter clearance techniques

A combination of two flushing methods is recommended to facilitate effective PICC flushing and locking objectives: use of a pulsatile flushing technique and the application of positive pressure at the end of the flush (Denton, 2016). This technique will differ if using a positive fluid displacement NFD. Use a brisk ‘push-pause’ flushing technique routinely when flushing the PICC i.e., flush briskly, pausing briefly after approximately each ml of fluid. The ‘push-pause’ technique causes turbulence within the catheter, which helps to flush away any debris and prevent occlusion of the lumen. Studies have shown that the resulting turbulent flow created by the push-pause technique is considerably more effective at rinsing the lumen, in comparison to a continuous laminar flow (Guiffant et al. 2012). This technique has also been found to significantly reduce catheter, bacterial attachment and growth in VADs. Never flush under resistance.

Syringe size

Where possible, do not use syringes smaller than 10 ml to flush a PICC. This is to reduce the risk of excessive pressure being exerted on the lumen which might cause it to rupture. Smaller syringes exert greater pressure however, syringe size alone is not sufficient to prevent rupture. When resistance is felt, if more pressure applied to overcome it, catheter fracture could result regardless of the syringe size. Smaller syringes can be used to administer medications as these are not delivered with any force.

If the catheter possesses a clamp, clamp the line while the final ml of the flush is being injected. If there is no clamp you can achieve a “positive pressure finish” by removing the syringe from the needle free device while injecting the last ml: but note that to avoid any spray from the syringe you should hold sterile gauze around the connector while doing this. Maintaining positive pressure helps prevent blood entering the catheter after flushing, which might lead to occlusion or thrombus formation. Once again, always consider the type of NFD in use and adjust your clamping sequence taking this into account.

‘Locking’ the PICC

There is insufficient evidence to suggest heparin-saline solution is more effective than 0.9% sodium chloride, in maintaining lumen patency and heparin has been known to cause serious adverse effects in susceptible patients (Alexander 2010; López‐Briz, 2014). Therefore, many institutions have stopped using heparin to ‘lock’ vascular access devices. Follow your local policy for locking guidelines.

Prior to PICC use

Aspirate a PICC prior to use to check for blood return, confirm patency, assess catheter function and prevent complications prior to administration of medications and / or solutions (Gorski, 2021; Denton, 2016). You should take further steps to assess patency of the device prior to administration of medications and / or solutions, for example diagnostic tests (Denton, 2016). If aspiration is not possible, this should be investigated as it could be caused by a fibrin sheath or inadequate catheter placement. Using a device with evidence of fibrin sheath could result in extravasation. Do not attempt to deliver medications if there is any resistance felt if the patient experiences pain during administration or if there is swelling or leaking at the site when the device is in use.

PICC measurement

Prior to use and at each dressing change, the PICC should be measured. This is to ensure that the tip of the catheter remains in the original position. This is an important step as the administration of vesicant or irritant medications into the smaller peripheral veins can result in extravasation or can lead to thrombosis. Therefore, it is important to continuously check that the tip of a PICC remains in the lower SVC or upper right atrium (Gorski, 2021).

When: The length of PICCs should be measured when care and maintenance is being carried out or if a patient is concerned that their device has migrated.

How: This measurement should be done from the same place documented on device insertion. This is usually from the insertion site of the PICC to the catheter hub. The external catheter length should remain the same as that documented on insertion.

Multi lumen PICCs

Always treat each lumen as a separate catheter as they have separate fluid pathways. Both lumens should be flushed when performing PICC C&M. If one lumen becomes occluded this should be investigated.

How do I take blood from a PICC?

PICCs and power injectors

Contrast media can be used in any CT compatible device up to the pounds per square inch (PSI) limit indicted for that device. The PSI limit varies by device, so it is important to check this prior to using any VAD for the delivery of drugs under pressure.

Conclusion

This article has provided an overview of the most important aspects of the care and maintenance of PICCs. It is important to always follow your own hospitals policies, procedures and guidelines.

The final article in this series will focus on how to deal with PICC complications.

References

- Clare, S., & Rowley, S. (2018). Implementing the Aseptic Non Touch Technique (ANTT®) clinical practice framework for aseptic technique: a pragmatic evaluation using a mixed methods approach in two London hospitals. Journal of infection prevention, 19(1), 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757177417720996

- Barton, A. (2020) Universal adhesive vascular access securement with Grip-Lok devices. British Journal of Nursing. 29(8), p.S28-S33

- Gorski et al (2021)

- Alexander 2010;

- López‐Briz, 2014

- Guiffant et al. 2012

- Baskin et al. 2012

- Mitchell et al. 2009

- Rowley S. (2001) Theory to practice: Aseptic non touch technique. Nursing Times 97: VI–VIII. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley S, Clare S. (2009) Improving standards of aseptic practice through an ANTT trust-wide implementation process: a matter of prioritisation and care. Journal of Infection Prevention 10: S18–S23. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley S and Clare S (2021) Right Asepsis with ANTT® for Infection Prevention in Vessel, Health and Preservation: The Right Approach for Vascular Access. Moreau et al (2021) Switzerland, Springer open. Available on line [Accessed June 2021] Vessel Health and Preservation: The Right Approach for Vascular Access | SpringerLink

- World Health Organisation (WHO). (2009) World Health Organization Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care: First Global Patient Safety Challenge Clean Care is Safer Care. Geneva: WHO; Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44102/1/9789241597906_eng.pdf (accessed May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Corley, A et., al (2017) Tissue adhesive for vascular access devices: who, what, where and when? British Journal of Nursing 26:19:S4-S17.=

- Nicholson and Hill (2019) Cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive: a new tool for the vascular access toolbox. British Journal of Nursing 28,19:S22.

If you liked this article, you might also like: