Behind every successful arterial line insertion lies a solid understanding of anatomy and site selection. This is critical to patient safety, procedural success, and long-term outcomes.

Long before the needle touches the skin, it is important to carry out a thorough patient assessment and provide clear communication to the patient. Arterial cannulation is an invasive procedure, therefore a structured pre‑procedural evaluation helps clinicians identify contraindications, choose the most suitable site, anticipate complications, and build trust with the patient or their family. Read more about these in our Mastering Arterial Line Placement Article Series: https://campusvygon.com/uk/mastering-arterial-line-placement/

Patient History and Pre-Procedure Evaluation

Key considerations include relevant medical history such as diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, Raynaud’s syndrome, or prior surgeries that may alter anatomy, as well as local factors like infection, burns, previous or recent arterial line placements, or the presence of AV fistulas or grafts. Clinicians must also evaluate the patient’s cognitive and physical ability to provide consent and cooperate with positioning.

Understanding the Foundations of Safe Arterial Cannulation

Arteries are composed of three distinct layers, each with a specific function and clinical relevance:

- Tunica Intima – The innermost layer facilitates blood flow and prevents the formation of blood clots. Trauma to this layer during cannulation can trigger platelet adhesion and thrombus formation.

- Tunica Media – The middle layer allows the artery to constrict and dilate. This layer is often responsible for vasospasm during attempts at cannulation.

- Tunica Adventitia – The outermost layer provides structural support and protection.

Understanding these layers helps clinicians minimise trauma during insertion and reduce complications like thrombosis or arterial spasm.

Selecting the Most Appropriate Insertion Site

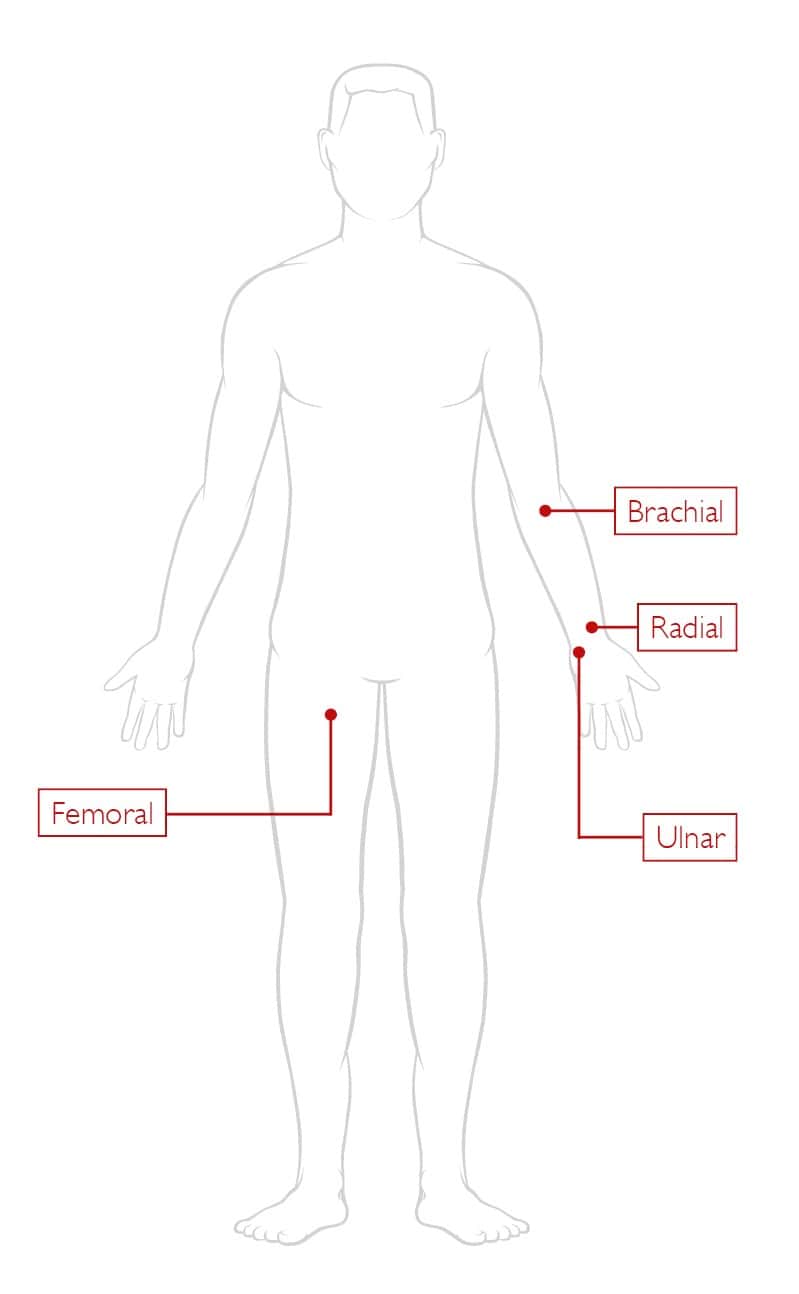

Not all arteries are created equal when it comes to cannulation. Here’s a breakdown of the most commonly used sites:

The radial artery is widely regarded as the gold standard site for arterial line placement because it is superficial, easy to palpate, and supported by strong collateral circulation through the ulnar artery. It is suitable for most adult patients in ICU or theatre environments. It is important to perform an Allen’s test beforehand to ensure adequate ulnar blood flow before cannulation.

The ulnar artery should be used with caution for arterial line placement, as it has traditionally been avoided due to being more difficult to palpate and carrying a higher risk of complications. However, with modern ultrasound guidance it has become a viable option, particularly in patients with ulnar-dominant circulation.

The brachial artery is larger and therefore generally easier to cannulate, but its lack of significant collateral circulation makes it a higher‑risk choice for arterial line placement. If occlusion occurs, it can result in serious limb ischaemia, so this site should be reserved for situations where alternatives are unsuitable.

The femoral artery is generally considered a last‑resort option for arterial line placement, reserved for emergencies or situations where peripheral access is not possible. Although it can be quick and reliable to access, it carries higher infection rates and the added risk of catheter fracture if the patient’s positioning is poor.

Ultrasound Approaches for Arterial Access

Ultrasound guidance is increasingly becoming the standard of care for arterial line placement because it improves first‑attempt success, reduces puncture attempts, and minimises complications.

Using a transverse view allows the artery to appear as a round, easily identifiable structure, while a longitudinal view provides real‑time visualisation of the needle entering the vessel. The technique relies on basic ultrasound physics, where high‑frequency sound waves reflect off tissues to create live images.

Effective probe handling is essential, with transverse views showing vessels as circles and longitudinal views showing them as lines. High‑frequency probes are preferred for superficial vessels to maximise resolution, and when used correctly with appropriate training, ultrasound not only increases procedural success but also enhances patient safety.

Proper Device Selection

Selecting the right arterial catheter for the right patient is essential for accurate monitoring and reducing complications, making device choice just as important as cannulation technique. Decisions should account for the patient’s indication for an arterial line, expected dwell time, and any underlying risks.

Although arterial lines are typically used for continuous blood pressure monitoring and frequent blood sampling, clinicians must also consider relative contraindications such as poor collateral flow, vascular disease, coagulopathy, or infection at the proposed site, in which case senior review is advisable.

Dwell Time

Dwell time influences selection of the appropriate device. Short-term use (hours to one or two days) may be adequately served by a standard over-the-needle cannula, whereas longer-term monitoring (several days) is better supported by a Seldinger catheter, due to its long length and reduced risk of dislodgement, it also offers greater stability and consistent waveform accuracy.

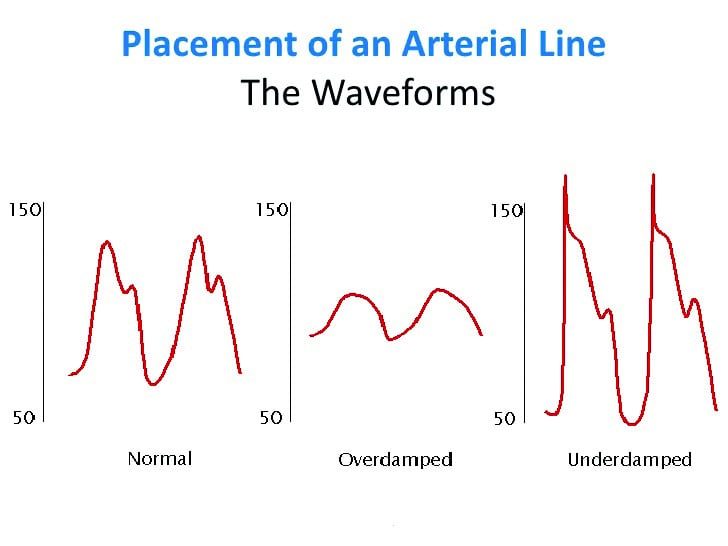

Signal Quality

Signal quality is another critical factor, as both over-damping and under-damping can distort blood pressure readings. Choosing the correct catheter gauge, ensuring compliant tubing (less rigid causing under-damping), and avoiding bubbles or kinks in the system (causing over-damping) all help maintain an accurate arterial waveform. For most adult radial lines, a 20G catheter provides a good balance between preserving vessel integrity and minimising the risk of thrombus.

Several device options are available, including classic Seldinger catheters designed with polyethylene for accurate waveform transmission, or simpler over-the-needle (non-Seldinger) arterial cannulas for quick deployment in routine cases. Whichever system is used, good practice includes matching catheter length and gauge to the patient, ensuring the system is fully primed and air bubble-free, and selecting a device that supports critical damping for accurate waveform. It is also important to consider blood sampling needs, as some systems are better suited for frequent draws. Thoughtful device selection not only enhances procedural success but also improves patient safety and monitoring reliability.

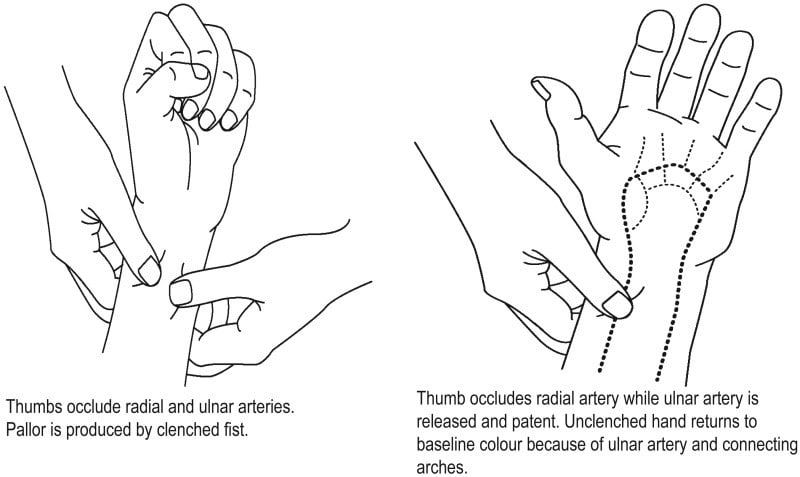

The Simple, but Vital Allen’s Test

Before radial artery cannulation, confirming adequate collateral circulation in the hand is essential, and the modified Allen’s test provides a simple bedside method.

While the patient has a clenched fist, occlude both radial and ulnar arteries with firm pressure, observe hand blanching as they open their fist, and then release the pressure on the ulnar artery. This test allows the clinician to quickly determine whether circulation returns within 15 seconds.

A positive test indicates it is safe to proceed on that side, whereas a negative test requires retesting on the opposite arm or using an alternative site.

Communication and Documentation

Alongside assessment, clear communication remains critical: patients or their families should be informed about the purpose of using the arterial line, what the procedure involves, potential risks, and how long the line may remain in place. In emergencies or when patients lack capacity, implied consent may be necessary but must be documented appropriately.

Finally, proper documentation ensures clinical transparency and continuity of care. Records should include assessment findings such as the Allen’s test result, the rationale for the chosen insertion site, the discussion around consent or the justification for implied consent, and any anticipated challenges or precautions. These steps lay the groundwork for safe, ethical, and effective arterial line placement.

Reducing Pain of Insertion and Appropriate Technique

Arterial line insertion is a skilled procedure which relies on thorough preparation, sterile technique, and a structured approach to ensure accuracy and patient safety. Whether using the direct puncture method or the most preferred Seldinger technique, clinicians must set up equipment correctly, position the patient, maintain aseptic technique, and methodically follow each insertion step. The Seldinger technique offers higher success rates and less trauma, making it especially valuable for patients with difficult access. Throughout the procedure, correct handling of guidewires, careful catheter advancement, and immediate confirmation of an accurate arterial waveform are essential for successful cannulation.

Effective pain management and patient reassurance play an important role in maintaining comfort during the procedure. Local anaesthesia, typically lidocaine 1% or 2%, should be infiltrated subcutaneously at the insertion site, with awareness of potential risks such as allergic reactions or accidental intravascular injection. Despite this, patients may still experience pressure or discomfort, so supportive communication is vital. Once the line is inserted, the clinician must zero the transducer and complete detailed documentation, including the site used, number of attempts, technique applied, and any complications. Mastering arterial cannulation involves not only technical precision but also consistent attention to safety, sterility, communication, and accurate record‑keeping.

Common Complications and How to Handle Them

Arterial cannulation is a routine and valuable procedure in critical care, but it carries important risks that clinicians must anticipate. Complications such as infection, air embolism, thrombosis, haemorrhage, accidental drug injection and haematoma can occur even when the technique is performed correctly. Safe practice relies on recognising early warning signs, maintaining strict aseptic standards, minimising unnecessary line manipulation and responding promptly when problems arise. By understanding how these complications develop and how they present, clinicians can intervene early and prevent minor issues from becoming serious events.

Each complication has distinct prevention and management strategies. Infection remains a major risk, emphasising the need for rigorous hand hygiene, appropriate antisepsis and secure fixation. Mechanical issues such as air embolism, occlusion and haemorrhage typically result from poor line setup or instability, highlighting the importance of secure connections and careful monitoring. Drug administration errors are entirely preventable through clear labelling and staff education. Haematomas can be avoided by applying adequate pressure after insertion or removal. With consistent adherence to best practice and ongoing staff training, arterial lines can be used safely and effectively while keeping complications to a minimum.

Ongoing Care and Maintenance of an Arterial Line

Ongoing maintenance of an arterial line is essential for preventing complications and ensuring accurate monitoring. Regular assessment of the insertion site, maintaining a closed system, keeping connections secure and clean, and following strict aseptic technique during any manipulation all play a crucial role in reducing infection and mechanical risks. For a detailed guide on best practice in post‑insertion care, maintenance and safe removal, you can read more here: https://campusvygon.com/uk/mastering-arterial-line-placement/article-7-post-insertion-care-maintenance-safe-removal/

Conclusion

Arterial cannulation is a vital tool in critical care, and its safety relies on clinicians recognising risks early, applying best practice consistently and responding quickly when complications arise. By combining meticulous technique, vigilant monitoring and thorough ongoing maintenance, healthcare teams can significantly reduce the likelihood of adverse events and ensure that arterial lines remain a reliable method of patient management.