The mechanical complications of an implantable port are numerous and frequent. However, they are often avoidable if the basic rules of insertion and use are known and respected.

We can classify the causes of mechanical complications of ports as follows:

– Catheter placement

– Port placement

– Huber needle placement

– Huber needle removal

– Complications independent of any technical error

In this article, we will illustrate our points with an iconography collected during our 25 years of experience, 12 of which were spent at the Paoli-Calmette Institute in Marseille where we founded the Vascular Access Unit in 2006.

I/- Port complications in relation to catheter placement

-

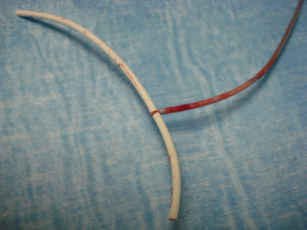

Fissuring or rupture:

We can observe a fissuring phenomenon or even rupture along the catheter path that takes place five centimetres from the port. It is most often due to the pinch-off syndrome that occurs during venous access via the subclavian vein in the costo-clavicular clamp and without ultrasound guidance.

Photo 1

Photo 1

Photos 2 and 3

Photo 4

Photo 4

-

Catheter-port disconnection

Catheter-port disconnection occurs when the catheter does not properly fit the port exit tube, or if the connection ring is incorrectly positioned or even inverted. Hyper pressure on an obstructed port with an attempt to unblock it can also lead to the disconnection.

Photos 5 and 6: Catheter-port disconnection

Photos 5 and 6: Catheter-port disconnection

-

Catheter leakage due to misconnection

Catheter leakage can be a catheter injury caused by the port exit tube and is related to misconnection between the catheter and the port through the connection ring. If it is not correctly connected according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, it can damage the catheter.

Photos 7 and 8

Photos 7 and 8

-

Absence of reflux during insertion

Absence of reflux during insertion can be observed when there is an excess of the catheter length, which is positioned lower than the cavoatrial junction and with a possible risk of arrythmia. To obtain perfect reflux, the catheter should be withdrawn over a few centimetres.

Also, to prevent this phenomenon, ECG or RX control is highly recommended.

-

Impossible injection during insertion

Two causes can possibly lead to an impossibility to inject during insertion:

- Coagulation of the catheter/port

- Kink in the catheter during port insertion

-

Injection and reflux are dependent on the arm position or the head rotation

If the injection and reflux are dependent on the position of the arm or the rotation of the head, the catheter is poorly positioned. Therefore, no tolerance should be accepted. The use of the device cannot depend on the body’s position.

II/- Complications in relation to the installation

- Port flip

A needle that does not meet the septum but immediately the metallic plane of the port base means that the port has turned over. Most of the time, the flip is due to the creation of a large port pocket.

An external manoeuvre that consists of pinching and folding the skin can be attempted to reposition it. If it is successful, leaving a Huber needle as a support for 5 days (depending on the patient’s conditions) can be useful. That will prevent another flip while fibrosis is created. If it is not the case, intervention to fix the port with stitches can be necessary to ensure its fixation.

To facilitate the passing of the stitches, we often tend to position the port close to the incision which can be dreadful in terms of infection. Any scar, however perfect it is, is a gateway for infection and under no circumstances should the Huber needle cross the scar to reach the septum. The septum should always be away from the incision. We therefore recommend creating a conical pocket (preferably with scissors) to bury the device at 4 to 5 cm. When the tip of the port is pushed towards the bottom of a pocket that was not too dissected, it creates a retention, and the port is held in place. Therefore, it can be possible to access the port without removing the dressing covering the scar.

The images below illustrate the position of the port in relation to the incision:

Photos 9 and 10

Photos 9 and 10

Photos 11 and 12

Photos 11 and 12

- Impossible puncture

Despite the use of the longest Huber needles, it is sometimes impossible to reach the bottom of the port or even to palpate the septum. In an overweight patient, it is due to the deep position of the port. In this type of patients, we recommend using a larger device and positioning it closer to the sternum.

- Skin erosion and/or explantation

Skin erosion and/or explantation is due to the port that has been positioned too close to the surface or in a cachectic patient. This can lead to infection. Moreover, this complication can be the consequence of an infection or a hematoma.

Photos 13 and 14

Photos 13 and 14

In photos 13 and 14, puncture was performed at the centre and more specifically, in a port too close to the surface and positioned in the centre of a cicatricial area.

III/- Port complications in relation to Huber needle’s placement:

In this part, we will address the most dreadful complication, which can sometimes be dramatic: extravasation.

There are several possible causes to extravasation:

– Misplacement of the Huber needle (the needle didn’t go through the septum)

– Poorly fixed needle under the dressing which leads to displacement

– Secondary displacement by traction on the tubing

– Wrong assessment of blood reflux (false reflux of dark blood)

The best approach is to hold the port with two fingers that stretch the skin over the septum (like a drum). The puncture must be perpendicular to the bottom of the port until you reach the bottom. Then, it is mandatory to check for blood reflux. It is sometimes obtained only after an injection of 1 to 2 mL of saline solution which unblocks the orifical fibrin. As soon as reflux is obtained, 10 to 20 mL of saline solution will be injected to check that it is painless and that no swelling is noticed around the port.

Despite these precautions and the professionalism of those involved, extravasation is still possible at any time. At the slightest pain, burning, itching, the infusion must be stopped and reported.

The consequences of an extravasation depend on the product involved.

Photo 15

Photo 15

In photo 15, the tubing connection between the patient and the IV pole got stuck under a door. The needle came out of the port but was unfortunately still in the patient’s skin. The drug was a highly vesicant product which led to cutaneous necrosis.

IV/- Complications in relation to the removal of the Huber needle:

The removal of the needle may be responsible for occlusion of the port and/or catheter if positive pressure (injecting saline while removing the needle from the port) is not performed.

Photo 16: Coagulated port

Photo 16: Coagulated port

Picture 17 shows how to remove the needle with positive pressure.

Photo 17

Photo 17

At the Paoli-Calmettes Institute in Marseille, we had a patient whose device was still functional despite not being used for eleven years. This was possible thanks to a perfectly performed positive pressure.

Keep in mind that regular flushing with Heparin is not necessary especially if positive pressure is well performed.

V/- “Inevitable” mechanical complications of ports:

The previous complications can be avoided by respecting good practices of placement, use and maintenance. However, others can occur despite respecting them and will be qualified as inevitable.

-

The impossible removal of the catheter

After a certain number of years in place, the removal of the port is always possible with or without incident. However, it is not always the case for the catheter.

In fact, after 8 to 10 years, the catheter can sometimes be impossible to remove. We can say that it is incorporated in the vein or “endothelialized”. It is included in the thickness of its wall and its removal is impossible. It will be left in place without any risk (like a pacemaker probe, for example). It is important to explain this to the patient and to obtain proof that they have been properly informed.

-

Secondary disappearance of reflux

In this paragraph, we will include two complications that should be considered when there is a disappearance of blood reflux after a few days, weeks or months of use.

There are two complications to look for if you can inject saline solution but cannot obtain blood reflux:

– Secondary displacement of the catheter

– The existence of a fibrin sleeve

A simple chest x-ray will provide information on the secondary displacement.

Photos 18 and 19

Photos 18 and 19

In the case of photos 18 and 19, it is imperative to replace the catheter before any chemotherapy and to position it lower towards the atrium while keeping the reflux zone. In some cases, the catheter should be completely changed. Special attention should be paid to patients who suffer from a thoracic pathology. In fact, during a mediastinal hyper pressure (violent effort of coughing), the catheter might turn over.

If the image had shown a catheter perfectly in place (tip of the catheter located two vertebrae below the carina), it would have been essential to inject a few mL of Iodine. It would have probably confirmed the existence of a fibrin sleeve.

Photo 20: Fibrin sleeve

Photo 20: Fibrin sleeve

Fibrin sleeve around a catheter is a natural phenomenon. The insertion of the catheter inside the vessel induces colonization by blood elements including fibrin.

According to a RAAD study, a fibrin sleeve is present on all catheters but does not lead to any complication. It only becomes problematic if it overflows towards the exit of the catheter. It may then behave like a non-return valve: injection is possible, but blood reflux cannot be obtained.

Photos 21 and 22

Photos 21 and 22

On photos 21 and 22, the iodine injected in the catheter goes up along the sheath. This sheath is fragile and shows what could be considered as a catheter perforation when in fact it is a leak in the sleeve.

Sometimes, the sleeve adheres to the endothelium making the catheter bend like a fishhook. Such a catheter should never be removed. An injection of fibrinolytics should rather be performed. It will most often within the hour allow the obtention of blood reflux.

It is important to keep in mind that it is impossible to know who will develop a fibrin sleeve. Most patients do not develop it, but some are more prone to it.

CONCLUSION:

Most incidents of implantable ports are linked to not respecting good practices for placement and use. Most often, mechanical complications can be avoided by respecting the guidelines.

Bibliography:

– Jean-Jacques Simon. November 4th, 2021 Conference on the best practices of implantables ports – Vygon.

– Ackermann M, Cosset-Delaigue MF, Kamioner D, Kriegel l. L’abord veineux de longue durée dans le cancer du sein. Dispositifs veineux implantables (DVI) : indications, pose et complications. Oncologie 2019 ; 11(12) : 621-34

– Pourreau Aurélie. Analyse sytémique des risques liés aux cathéters. Thèse ENSM. Mars 2008.